Mongol Rule: From Terror and Destruction

to Law and Order

I. Rise of the Mongols

•Genghis Khan

A coalition of Mongol clans and tribes pronounced Temujin (b. 1167) “Genghis Khan” at a “quriltay” in 1206

•Almost immediately Genghis Khan launched campaigns aimed at lands beyond Mongolia

II. Genghis Khan and His Time

•The Mongolian Plateau had many tribes, probably more Turkic ones than Mongol ones

•An earlier group, the Khitans, had become a “Chinese” dynasty, Liao, ruling north China; it was replaced by a Tungus group, Jurchen, who originated from the Khingan Mountains, to the east of Mongolian Plateau, and established their own “Chinese” dynasty, Jin.

•The Gansu Corridor was no longer in the hands of the Uighurs, but controlled by a Tibeto-Burman group called Tangut; they also established a “Chinese” dynasty, West Xia (Xi Xia) which ruled the western part of north China

•Southern Sung Dynasty was experiencing a new phase of economic and intellectual growth

•In the southwest, Tibet was in retreat since it was forced out of Xinjiang and the Gansu Corridor in the 11th century

•In Xinjiang, the Turfan area saw Uighurs in firm control of a Buddhist kingdom, but many Turkic groups were Manicheans and Nestorian Christians

•Further west, a Khitan prince fled the Jurchen onslaught and established Karakhitay in the Chu River area, then expanding to most Central Asia

•An also expanding Khwarazm controlled Transoxania, Khurasan and Ferghana, attempting to make initial contact with the Mongols

•In Iran and Iraq, the Seljuks were still powerful and the Abbasid Caliph was under the sway first of the Seljuks and later the Khwarazmians.

•In Asia Minor, the Seljuks were firmly established as the dominating ethno-religious group

•The Byzantine, though weakened by the Seljuks and the Crusaders, still had considerable strength left

•In the Levant (Lebanon, Palestine, part of Syria), the crusaders and Muslims each controlled some cities and towns

•To the north, the Russian steppe saw many nomadic groups pass through

•The political grouping of the Slavs was centered around Kiev; Moscow was still just a small town

•The Poles and Hungarians, both belonging to the Latin church, had their own monarchs

•Western Europe was undergoing a slow revival from the Dark Ages with economic and cultural growth

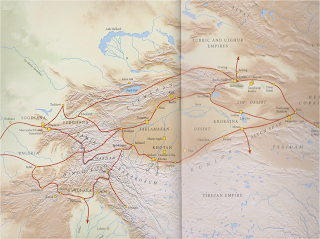

III. Mongol Wars of Expansion

A.Phase One (1219-1223):

•Conquered Xi Xia in 1209, took Beijing in 1215 and entered Turfan

•The Turfan ruler surrendered voluntarily; many Uighurs thus entered Mongol service, enabling the latter to rule with more administrative skills

•A Naiman (hostile to Genghis Khan) prince worked from within Karakhitay to subvert it in secret collaboration with Khwarazm, thus making the latter in close contact with the Mongols

•Story of the Mongol embassy to Khwarazm—giving Genghis Khan a motivation for revenge and going farther west than he had planned

•Looting Bukhara, massacre in Samarkand and crushing Khwarazm

•Rounding the Caspian Sea, entering Caucasus, conquering Georgia and encountering Russia (Rus).

B. Phase Two (1237-1242):

•Led by Batu, the eldest son of Juchi, known as “Expedition of the Eldest Sons’,

•The Mongol forces penetrated deep in Russia, demolishing the Russian principalities;

•Sacking Kiev in 1240, indirectly contributing to the rise of Moscow

•Advancing to Poland and Hungary, then to the east coast of Adriatic Sea

•Upon hearing the death of Guyuk, Batu returned east and set up the Golden Horde (Kipchak) Khanate in Saray, in the middle Volga region

C. Third Phase (1253-1260):

•Once becoming the Great Khan, Monge ordered his brother Hulagu to lead another expedition force

•Hulagu in 1256 demolished the base of the Ismailist “Assasins” at Alamut, not far from Tehran to clear the way; then the Mongol forces took Baghdad in 1258, putting the Caliph to death and ransacking Baghdad, ending the 500-year Abbasid dynasty and changing the landscape of the Islamic world

•Taking Damascus in 1260 but defeated by the Mamluks to the north of Jerusalem; Mongol forces thwarted after this defeat

•On knowing that Kubilai had become the new Great Khan, Hulagu set up Ilkhanate, covering territories west of Amu Darya and east of the Tigris, with its capital in Tabriz

IV. The Mongol Empire

A.Yuan China (1279-1368)

B.Ulus Chaghatay (1225-1370)

C.Golden Horde (1243-1361)

D.Ilkhanate (1261-c.1400)

# Ulus Ogedey (1251-1310), divided by Golden Horde and Chaghatay

V. Forced and Unintended Globalization

A.Territories, Populations, Products and Trade

B.Roads and Postal System

C.Administrative Measures

D.Cultural Exchange

E.Migration

F.Plague

VI. Mongol Diplomacy

A.Mission of Carpini in 1245

•Pope Innocence IV wanted to stop the Mongol advance by diplomacy, in the hope that the Christians in the Mongol Court would offer help

•He sent a Franciscan priest, Carpini, to Saray with a letter; Batu sent him to see the Great Khan in Karakorum

•The mission ended in failure, with Carpini bringing back a letter in Mongolian rejecting the Pope’s appeal; he later wrote a book detailing his observations along the way.

B. Mission of De Rubrouck in 1253

•While in Cyprus during his crusade, King Louis IX sent a French priest to the Mongol Court, hoping to establish an alliance with the Mongols against the Muslims

•De Rubrouck was helped along the way by Christians and also saw many Christians in the Mongol capital, some were merchants, some served in the court, others were captives

•His mission also failed

C. With the French Court in 1289

•The Khan of Ilkhanate proposed, through a Greek merchant, to the French king, Philippe Le Bel, to join forces in attacking Jerusalem and split the spoils

•When the letter arrived in Paris, Philippe Le Bel had died; the merchant returned to report his mission, only to learn that the letter writer had also died

VII. Seafaring on Horseback

•The Mongols established extensive navigational routes once they conquered Southern Sung

•Trade via sea routes advanced greatly during Yuan dynasty

•The Mongols tried to invade Japan, but failed due to bad weather

•They also tried to attack Indonesia, again without success

•The commander of the Mongol navy was an Uyghur

VIII. The Winning Secrets of the Mongols

(Since these are secrets,they cannot be told here)

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

LECTURE 7 / 24 NOVEMBER 2009

Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity and Judaism in Tang and Song China

I. Zoroastrianism, a Religion of Dualism

A. Zoroaster (628-551 BCE)

Born in a family of priests near today’s Tehran

Good and evil in constant struggle; Sun and Fire are symbols of Good (Mazda)

Those who live by the principles of the Good ascend to heaven after death; those who act falsely and evilly descend to hell after death

His teachings were contained in “Avesta”, first compiled in 6th century BCE, incorporating the epics of Iran

It had an inclination for monotheism and was a form of salvation religion.

It became the state religion of Sassanid Persia

B. Spread of Zoroastrianism to the Entire Persian World and Sogdiana

I. Zoroastrianism, a Religion of Dualism

A. Zoroaster (628-551 BCE)

Born in a family of priests near today’s Tehran

Good and evil in constant struggle; Sun and Fire are symbols of Good (Mazda)

Those who live by the principles of the Good ascend to heaven after death; those who act falsely and evilly descend to hell after death

His teachings were contained in “Avesta”, first compiled in 6th century BCE, incorporating the epics of Iran

It had an inclination for monotheism and was a form of salvation religion.

It became the state religion of Sassanid Persia

B. Spread of Zoroastrianism to the Entire Persian World and Sogdiana

C. Zoroastrianism among the Nomadic Tribes and in China in 6th Century

Zoroaster temples were built in Chang’an, Luoyang and many other Chinese cities; the Tang court set up a special office headed by a “sabao” to regulate and manage the Zoroastrian affairs

Severely set back after 845 when the Tang Emperor Wu-zong decreed to curtail all religions of non-Chinese origin

But Zoroastrian temples still existed in many Chinese cities in Song Dynasty

No more records of its activities after the Mongol invasion

II. Manichaeism, a New Religion of Dualism

A. Mani (215-277 CE)

Born in Mesopotamia and a Zoroastrian follower at first, Mani started to propagate a new religion at age 24 after he saw the twin angels in a dream and later told by the angels to found a new religion and be a messenger for Light

Teaching a form of dualism with “two principles and three phases”.

Two principles: Light and Darkness were the bases of the universe

Three phases: an “early phase” before the world was created when Light and Darkness coexisted; an “intermediate phase” in which Light and Darkness struggle constantly and repeatedly; and a “final phase” in which Light and Darkness are forever separated whereby Light becomes utter light and Darkness extreme dark

This dualism is in fact a synthesis of Zoroastrianism, Buddhism and Christianity

Despite a leg impairment, Mani traveled widely, having been to Central Asia, Kashmir, India and Tibet, to proselytize this religion

Manicheans did not eat meat, were divided into vowed believers and regular believers with the former observing more stringent rules and the latter paying to support the former

He aroused hatred by the Zoroastrians and was put to death

B. After Mani’s death, many Manicheans fled to Central Asia and India, spreading the religion in a manner similar to the spread of Christianity after Jesus was crucified

C. Manichaeism gained many converts from Zoroastrians after Sassanid Persia fell to the Arab forces

D. Many Sogdians converted to Manichaeism and introduced the religion to the nomadic Turks as well as to Buddhists in Khotan, Turpan, Dunhuang, Chang’an and elsewhere in China

The Tang government did not like the teachings and practices of Manichaeism but allowed the followers to practice their religion

Manichean scriptures were translated into Chinese and there were large numbers of followers in many parts of China

Received a boost after the Uighurs helped Tang court crush the An Lu-shan rebellion and entered Chang’an en masse in 760 CE

The demise of the Uighur Kingdom in 840 CE and the interdiction by the Emperor in 845 CE of all religions except Taoism dealt a heavy blow to Manichaeism in China, but the spread continued in the form of a secret society or cult among the urban lower-class and the peasants

It almost took the path of Buddhism and merged with the Chinese culture; furnishing an ideology and a means of mobilization in several major peasant revolts in 10th to 12th centuries

E. The Mani script was created after the old Syrian alphabet in order to write the scriptures in Uighur language; many such scriptures have been found in Dunhuang, Kocho and other sites in Central Asia and Mongolia

F. Manichaeism was also at one time popular in North Africa; St Augustine was a believer in Mani before he became a Christian bishop and a major theologian of the Christian faith

III. Nestorian Christianity

A. Nestorius, born in Syria and once abbot of a monastery in Antioch, became the patriarch of Constantinople in 428 CE

B. He believed that (1) Jesus was human, born by Mary, God merged with Jesus to act as Son of God, the redeemer and savior; (2) therefore, Mary cannot be called Mother of God; (3) Christ had a dual nature, a man with a visible form and an invisible and formless Son of God; (3) thus Jesus is not God but an instrument of God.

C. At the Ecumenical Council held in Ephesus (Efes) in 431, he was condemned and forbidden to take the pulpit; Nestorius fled to Persia and formed his own church there

D. The Persian Nestorian-Christians propagated this religion to the Sogdians, Indians, etc.

E. The Nestorians also used an old Syrian alphabet to write their Bible which was almost identical in content to the official Christian bible compiled after the Council of Nicaea (Iznik) in 325

F. Nestorian Christianity in China

It entered China in 635 CE after the Emperor Tai-zong personally approved its setting up a church and the ordination of priests in Chang’an

At first the place of worship of the Nestorians was known as the “Persian Temple” since the priests were Persian, but later it was changed to “Roman Temple”

Nestorian churches were built in many Chinese cities

In 1624, a stele was discovered near today’s Xian; it was bilingual and gave detailed information about the spread of Nestorian Christianity in Tang China

In 20th century, many manuscripts were found in Dunhuang and Khotan, including prayers, hymns and paintings

The church maintained close relationship with top officials of Tang, and benefitted much from this association; but also suffered heavily when Tang Dynasty ended

It co-existed with Buddhism to the point that some of its priests participated in the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese

Along with Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity was recognized in Tang China as one of the “three foreign religions”, thereby banned in the “Anti-Buddhist” movement of 845 CE.

Since Buddhism had already become a part of Chinese culture and totally indigenized, it recovered from the crush in just a few years whereas the other three religions suffered long-term damages

IV. Judaism in China

A group of Jews came from Baghdad to the Song capital Bian-liang (present-day Kaifeng in Henan Province) in 11th century

Local people could not distinguish them from the Arab Muslims since the Jews also spoke Arabic, looked the same as the Arabs and did not eat pork

Nonetheless, the Jews had their own religious life with temples and rabbi who could read the Torah and presided over services on Sabbath

However, the Jewish community in China at some point decided to send their children to learn the Chinese classics in order for them to gain entry to officialdom or the literati class.

This made the educated Jews no longer observant in their ancestral religion

By 16th century, the Jewish community in China had only one synagogue left and no rabbi who could read the Torah, thus ceased to exist as a religious community

Some members of this community had become ministers and authors

This is a well-documented unforced disappearance of a Jewish community in the Diaspora

V. Summary

Buddhism was by far the most dominant, religion along the Silk Road and in China.

Zoroastrianism was practiced by Sogdians, and accepted by some nomads and other residents along the Silk Road.

After 6th century, Manichaeism made great inroads among the Turkic groups on the Mongolian steppe.

Evangelical work by Nestorian priests also converted some nomads on the Mongolian steppe as well as Chinese cities.

As the Cyrillic alphabet was invented for the Slavic converts to Christianity, so Mani script and Nestorian script were created for the nomadic converts.

After the An Lu-Shan Rebellion in China, both Buddhism and Taoism gained a large following among the ordinary people as well as the ruling nobles

A few emperors favored Buddhism while a few others favored Taoism.

Religious jealousy between Buddhism and Taoism was acute; that between Buddhism and Manichaeism was also common

By the 9th century, the Buddhist temples held large tracts of farm land and attracted many able men and women to abandon secular life and enter monastery life, having a negative impact on the economy.

A Taoist priest convinced Emperor Wu-zong to issue an imperial decree on “extinguishing Buddhism” and other non-indigenous religions

Some 4,000 Buddhist temples were destroyed, 40 million hectares of farmland owned by the temples were confiscated, and more than 260,000 monks and nuns were forced to return to secular life; this was one of two such anti-Buddhist movements in Chinese history

Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity thus suffered greatly; some 3,000 priests in Chang’an were forced to abandon their churches or temples.

On the Mongolian steppe, the Uighurs who were Manicheans were forced by a new group from the north to migrate to the Gansu corridor and today’s Xinjiang.

Uighur became the rulers of much of Xinjiang by the 10th century ; they also converted to the Buddhist religion of the people whom they ruled.

The departure of Manichean Uighurs from the Mongolian steppe after 840 left a religious vacuum

Many Nestorians fled to the Mongolian steppe after 845, filling the vacuum by converting the newly grouped Mongol tribes to Nestorian Christianity

Thus the Mongol script was also based on the Sogdian script, even after their conversion to Buddhism in 12th century

Both Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity persisted in the Chinese provinces but only thinly populated

Saturday, November 14, 2009

READINGS FOR MIDTERM

Stearns - Chapters 4, 5, 17

China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization - Chapters 3, 18, 19, 21

Encounters - Chapters 4, 9, 11, 14

The History and Civilization of China - pp. 1-108

Two articles and a map at Hisar Copy Center under the course name

China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization - Chapters 3, 18, 19, 21

Encounters - Chapters 4, 9, 11, 14

The History and Civilization of China - pp. 1-108

Two articles and a map at Hisar Copy Center under the course name

LECTURE 5 / 12 NOVEMBER 2009

From Samarkand to Chang’an: The Itinerant Sogdians

I. The Ancient Sogdian Letters

I. The Ancient Sogdian LettersIn 1907, under a Han dynasty watchtower northwest of Dunhuang, the Hungarian-British Archeologist Aurel Stein found a mail bag containing 8 letters written in the Sogdian language; 3 of them were too fragmented to read but 5 were relatively intact

B. Stein turned these letters to the British Museum; experts in the Museum and other experts began to try to translate them

C. After several trials and improvements over the past 100 years, we now know the complete content of these 5 letters

D. They were written by Sogdian merchants in 312 CE to other Sogdian merchants on the Silk Road or to their families in Samarkand

II. Who Were the Sogdians?

Sogdians were farming and trading people who lived in the Zarafshan River Valley in today’s Uzbekistan and spoke an Eastern Iranian language

They were ruled by Archamenids from Persia in 5th century BCE, Alexander (and the Seleucid Greek kingdom), and the Kushans.

Even though the Sogdians never had a united and strong kingdom of their own, they were very visible in Central Asia throughout its history.

III. The Rise of Sogdian Merchants on the Silk Road and Elsewhere

From 3rd to 10th century CE the dominant traders on the Silk Road were the Sogdians whose reach encompassed the Byzantine Empire, India and China.

Before the rise of Sogdians, Indians and Persians were prominent in the trade in Eurasia.

This may have been caused by the disruptions brought by Xiongnu’s westward and southward thrust, creating a vacuum for the Sogdians to fill in the central region of the Eurasian continent.

Therefore, not only were the Sogdians prominent in trade with China, but they were also active in South Asia and West Asia

IV. The Master Traders on the Silk Road

The ancient Sogdian letters give clear evidence that trade along the Silk Road mostly took place between Sogdian merchants some of whom were resident in various countries.

Since the Sogdians did not have their own currency, the common medium for trade was the Sassanian gold coins until the 7th century when Tang Chinese coins became the common currency in trade on the Silk Road.

Sogdian merchants brought spices, glassware, jewelry, medicinal material from the West to the East; they brought silk, tea and lacquerware.

They also traded rare animals, slaves, even singers, dancers and acrobats.

V. Sogdian Communities Along the Silk Road and in Eastern China

As trade developed, many Sogdians chose to stay in trading centers, forming their own community and having their own governing system as well as religious institutions (mainly Zoroastrian temples).

Historical records and archeological findings indicate at least 30 such communities from Kashgar in the west end of today’s China to Liaoning province in the northeast.

The leader of a Sogdian trade caravan was called a Sartpaw; the community leader of resident Sogdians was known by the same title.

This quasi autonomous communities often had their own armed forces, religious clergy and other administrative arrangements including the community coffer.

VI. The Integration of Sogdian Communities in the Chinese Society

The Sogdians were identified in Chinese historical records and other documents in the 3rd century.

Sogdians were also recruited into the army and often served in the imperial palace.

Almost all of the Sogdians who stayed in China took one of nine of the existing Chinese surnames; therefore, they were also known in China as a group of people with these nine surnames (“zhao-wu jiu-xing”).

During Tang dynasty, the Sogdians were known as good musicians and dancers; many of the roughly 3000 wine shops in Chang’an were run and staffed by Sogdians.

E. The central Chinese governments began to appoint the Sogdian community leaders as local officials with the title “Sabao”, the Sinicized version of Sartpaw.

F. During Sui and Tang periods, these Sogdian communities were integrated into the local administrative structure as regular “Xiang’s” or “Li’s”. (乡里)

G. Those Sogdian families who stayed in China long enough gradually became indistinguishable from the other Chinese.

VII. Contributions of the Sogdians to China

In addition to music and dance, the Sogdian clothing style became fashionable during the Tang dynasty.

Some rare animals from Africa and other places were introduced by Sogdians.

Sogdians brought their religious practices as well as artifacts which were merged in Chinese Buddhism.

The Sogdian script was later borrowed by the Uyghurs, Mongols and Manchus successively in their own writing system.

The Sogdian merchants greatly enhanced Chinese economy, enriching the material life in China.

Sogdians were mainly or at least partially responsible for the introduction of Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, and Nestorian Christian faith in China.

VIII. The Most Infamous Sogdian in Chinese History

An Lu Shan (Roxan) was born in China of Sogdian parentage; he became a regional military commander in northeast China.

During the reign of Tang Xuan Zong An Lu Shan, though very trusted by the emperor, started a rebellion which nearly toppled the Tang dynasty and caused decline of Tang power from the point onward.

His rebellion was defeated by the Tang forces with help from the Arabs and Uyghurs.

An Lu Shan has since been a household name in China, in a negative sense.

LECTURE 4 / 3 NOVEMBER 2009

I. Two Examples of Revisionist History

A. An Early Christian Community in China [by HKC]

Ban Chao dispatched his associate Gan Ying to visit Roman Empire (97 CE); Gan reached the Persian Gulf but was told by the Persians that it was too dangerous to cross the turbulent sea; therefore, he returned without getting to the Roman Empire

A. An Early Christian Community in China [by HKC]

Ban Chao dispatched his associate Gan Ying to visit Roman Empire (97 CE); Gan reached the Persian Gulf but was told by the Persians that it was too dangerous to cross the turbulent sea; therefore, he returned without getting to the Roman Empire

B. Reason for Zhang Qian’s Mission

Grotto Painting in Dunhuang done in 4th century

Depicting the scene of Zhang Qian departing China with Emperor Wu bidding him farewell

Han army captured a huge statue, “Golden Man”, from Xiongnu who worshipped it because it was a statue of Buddha from the West

Therefore Emperor Wu sent Zhang Qian to the West in order to learn more about Buddha

Since Buddhism was the dominant religion in Central Asia and India at the time of Zhang Qing’s mission and since Zhang Qian was inquisitive about the region, e.g., commerce between Bactria and India, it was possible that Zhang Qian learned about Buddhism and reported this to the Emperor; but this was not recorded in the official history on his mission

At any rate, Zhang Qian could only have learned of Buddhism after he arrived in the Western Region

Buddhists did not make or worship statues of Buddha until the Kushan Period which began more than 100 years after Zhang Qian’s death

II. Monks from the West to China

A. Parthamasiris (c. 100 CE)

Prince of Parthian Persia, lost to his uncle in the succession and took the throne of Armenia; when Romans conquered Armenia, they proposed Parthamasris to be King of Parthian Persia.

Objections from the Persians forced him to seek solace as a monk in Buddhism

He was an erudite man and able to achieve a high-level understanding and interpretation of Theraveda (Hinayana) Buddhism

Coming to China c. 140 CE, he mastered the Chinese language in just a few years

In charge of translating Theraveda scriptures for 23 years (148-171 CE) and starting a new style of Chinese prose

Taking refuge in southern China during the turmoil at the end of Han Dynasty and died there

B. Lokaksin

A Yue-chi, arriving in the Han capital toward the end of Han Dynasty

Translated scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism for over 10 years (178-189 CE)

Disappeared from public view after this work

C. Kumarajiva (344∼413 C.E.)

Father was an Indian noble, mother was a princess of Qiuci (Kucha)

Followed his mother to a nunery at age 7

Became learned at a young age; well versed in Theraveda Buddhism and gained a wide reputation not only in Central Asia but also in China

After he declined to come to Chang’an to serve a ruler at the time, he was forcibly taken to inside the Chinese border by the ruler’s army (382 CE) and stayed 18 years near the border even after the ruler himself was disposed

In 401 CE he was taken to Chang’an by a new ruler and provided with a team of 120 Chinese monks to assist him in translating the Mahayana Buddhist works

Over 600 volumes were completed during his time

He was credited for a new method of translation which is relevant even today

Founded a new school of Buddhist philosophy which resulted in a new sect

Admired as a genius, he was “ordered’ by the ruler to marry ten maidens so that his talent can be inherited

III. Chinese Monks to the West

A. Zhu Shiheng (c. 250 CE)

First Chinese monk to go west in search of true Buddhist scriptures

Confused about the Buddhist literature’s correctness and authenticity, went to Khotan (Yu-tian) to learn more

Obtained 90 volumes and sent them back to Luoyang after overcoming difficulties

Died in Khotan at age 80

B. Fa Hsian (Fa Xian)

Born in 334 and died in 420 C.E.

Decided to become a monk when his parents both died

First Chinese monk to go to India

He was 60 when he started his long journey in the company of 10 Chinese monks

Took 6 years to reach Central India, stayed there for 6 years to learn the language and the scriptures, 2 years in the south, including today’s Sri Lanka, and 1 year to return home by sea

Wrote “Buddist-Country Records” after his return, detailing his experiences

A compendium of Buddhist temples, practices, geography and history of Central Asia and Indian

C. Sung Yun

A native of Dunhuang, worked in the capital city of Luoyang in early 6th century

Was sent by the Empress Dowager of the ruling dynasty to the West to present gifts and seek better scriptures (518 CE)

Reached Khotan and the Pamirs by passing through many small states

IV. The Story of Xuan Zang

Born (602 CE) into a family of intellectuals and officials

Entered monastery at 13 and became a ordained monk at 21

Spending five years visiting many Buddhist scholars and learned major classical Buddhist works

Puzzled by differences in these works regarding the ways to reach nirvana, decided to seek truth from India despite the dangers and difficulties involved

Upon return he was offered a ministerial post but declined; was given resources by the Emperor to translate the books he brought back

His style was much more fluid and elegant than the previous translators

But he was far more than a translator of Buddhist scriptures

He compiled, with the help of his disciple, a book on the West at the request of the Tang Emperor and gave vivid and detailed accounts of some 138 states he had visited

He was also the founder of the new Buddhist school based on the new philosophy he had helped to form while in India

The Great Tang’s Records of the Western World (Ta-Tang-Si-Yu-Ki)

On Xuan Zang’s Return to Chang’an

Xuan Zang stated that he saw this and described its precise location

Archeological work was done in early 20 century to uncover it

Asoka’s Pillar near the birthplace of Buddha

Erected around 300BCE; excavated around 1910

V. Impact of Buddhism in China

Introduced into China in the turbulent times in Chinese history; gained acceptance and grew in influence during the 400 years of turmoil in northern China

Buddhism, along with Taoism, provided comfort and a hope of after-life to people who suffered

Many rulers of the northern regimes were non-Han; they needed a form of worship that was different from Confucianism and Taoism

As a result, Buddhism took Chinese a characteristic; Theraveda which focused more on the individual was overlooked, Mahayana which emphasized helping others to achieve nirvana become the standard Buddhism in China, hence, Korea, Japan and Vietnam

Buddhist and Chinese philosophy influenced each other, resulting in transformation of both; in terms of Buddhism, it was the Zen school of Buddhism

VI. Between Body and Soul

Biological being and social being

Instinctive being, intellectual being and emotive being

Religion of salvation and religion of transcendental meditation

For discussion: What motivated the early Buddhist monks and what gave them strength?

Depicting the scene of Zhang Qian departing China with Emperor Wu bidding him farewell

Han army captured a huge statue, “Golden Man”, from Xiongnu who worshipped it because it was a statue of Buddha from the West

Therefore Emperor Wu sent Zhang Qian to the West in order to learn more about Buddha

Since Buddhism was the dominant religion in Central Asia and India at the time of Zhang Qing’s mission and since Zhang Qian was inquisitive about the region, e.g., commerce between Bactria and India, it was possible that Zhang Qian learned about Buddhism and reported this to the Emperor; but this was not recorded in the official history on his mission

At any rate, Zhang Qian could only have learned of Buddhism after he arrived in the Western Region

Buddhists did not make or worship statues of Buddha until the Kushan Period which began more than 100 years after Zhang Qian’s death

II. Monks from the West to China

A. Parthamasiris (c. 100 CE)

Prince of Parthian Persia, lost to his uncle in the succession and took the throne of Armenia; when Romans conquered Armenia, they proposed Parthamasris to be King of Parthian Persia.

Objections from the Persians forced him to seek solace as a monk in Buddhism

He was an erudite man and able to achieve a high-level understanding and interpretation of Theraveda (Hinayana) Buddhism

Coming to China c. 140 CE, he mastered the Chinese language in just a few years

In charge of translating Theraveda scriptures for 23 years (148-171 CE) and starting a new style of Chinese prose

Taking refuge in southern China during the turmoil at the end of Han Dynasty and died there

B. Lokaksin

A Yue-chi, arriving in the Han capital toward the end of Han Dynasty

Translated scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism for over 10 years (178-189 CE)

Disappeared from public view after this work

C. Kumarajiva (344∼413 C.E.)

Father was an Indian noble, mother was a princess of Qiuci (Kucha)

Followed his mother to a nunery at age 7

Became learned at a young age; well versed in Theraveda Buddhism and gained a wide reputation not only in Central Asia but also in China

After he declined to come to Chang’an to serve a ruler at the time, he was forcibly taken to inside the Chinese border by the ruler’s army (382 CE) and stayed 18 years near the border even after the ruler himself was disposed

In 401 CE he was taken to Chang’an by a new ruler and provided with a team of 120 Chinese monks to assist him in translating the Mahayana Buddhist works

Over 600 volumes were completed during his time

He was credited for a new method of translation which is relevant even today

Founded a new school of Buddhist philosophy which resulted in a new sect

Admired as a genius, he was “ordered’ by the ruler to marry ten maidens so that his talent can be inherited

III. Chinese Monks to the West

A. Zhu Shiheng (c. 250 CE)

First Chinese monk to go west in search of true Buddhist scriptures

Confused about the Buddhist literature’s correctness and authenticity, went to Khotan (Yu-tian) to learn more

Obtained 90 volumes and sent them back to Luoyang after overcoming difficulties

Died in Khotan at age 80

B. Fa Hsian (Fa Xian)

Born in 334 and died in 420 C.E.

Decided to become a monk when his parents both died

First Chinese monk to go to India

He was 60 when he started his long journey in the company of 10 Chinese monks

Took 6 years to reach Central India, stayed there for 6 years to learn the language and the scriptures, 2 years in the south, including today’s Sri Lanka, and 1 year to return home by sea

Wrote “Buddist-Country Records” after his return, detailing his experiences

A compendium of Buddhist temples, practices, geography and history of Central Asia and Indian

C. Sung Yun

A native of Dunhuang, worked in the capital city of Luoyang in early 6th century

Was sent by the Empress Dowager of the ruling dynasty to the West to present gifts and seek better scriptures (518 CE)

Reached Khotan and the Pamirs by passing through many small states

IV. The Story of Xuan Zang

Born (602 CE) into a family of intellectuals and officials

Entered monastery at 13 and became a ordained monk at 21

Spending five years visiting many Buddhist scholars and learned major classical Buddhist works

Puzzled by differences in these works regarding the ways to reach nirvana, decided to seek truth from India despite the dangers and difficulties involved

Upon return he was offered a ministerial post but declined; was given resources by the Emperor to translate the books he brought back

His style was much more fluid and elegant than the previous translators

But he was far more than a translator of Buddhist scriptures

He compiled, with the help of his disciple, a book on the West at the request of the Tang Emperor and gave vivid and detailed accounts of some 138 states he had visited

He was also the founder of the new Buddhist school based on the new philosophy he had helped to form while in India

The Great Tang’s Records of the Western World (Ta-Tang-Si-Yu-Ki)

On Xuan Zang’s Return to Chang’an

Xuan Zang stated that he saw this and described its precise location

Archeological work was done in early 20 century to uncover it

Asoka’s Pillar near the birthplace of Buddha

Erected around 300BCE; excavated around 1910

V. Impact of Buddhism in China

Introduced into China in the turbulent times in Chinese history; gained acceptance and grew in influence during the 400 years of turmoil in northern China

Buddhism, along with Taoism, provided comfort and a hope of after-life to people who suffered

Many rulers of the northern regimes were non-Han; they needed a form of worship that was different from Confucianism and Taoism

As a result, Buddhism took Chinese a characteristic; Theraveda which focused more on the individual was overlooked, Mahayana which emphasized helping others to achieve nirvana become the standard Buddhism in China, hence, Korea, Japan and Vietnam

Buddhist and Chinese philosophy influenced each other, resulting in transformation of both; in terms of Buddhism, it was the Zen school of Buddhism

VI. Between Body and Soul

Biological being and social being

Instinctive being, intellectual being and emotive being

Religion of salvation and religion of transcendental meditation

For discussion: What motivated the early Buddhist monks and what gave them strength?

LECTURE 2 / 15 OCTOBER 2009

I. Prelude

A. General Remarks

1. History is a function of geography; take China as an example

2. To understand history it is necessary to study not only the historical documents, which often record political events, military conflicts and diplomatic treaties, but also archeological findings, which provide material proof of the way a certain group lived. Historians also have to concern themselves with art and literature, linguistics and anthropology, trade and commerce, religious beliefs and social customs, technological development and economic conditions. Most importantly, it is necessary to examine the causality between different events and the circumstances that either strengthened or weakened the causality.

B. Consequences of Alexander’s Eastward Thrust

1. The Greeks in Bactria: Agents of East-West cultural exchange and fusion.

2.The Yue-chi (Tocharians):The exiles who became accidental conquerors and propagators of Buddhism to Central Asia and China.

II. The Use of Horses by Nomadic Peoples

Domestication of the horse gave the chariot and horse-riding warriors a huge advantage in battle. Shepherds on horseback could supervise much larger herds than on foot. Horse was until the train the fastest means of transport and communication.

Speed of the horse made long-distance trading easier.

The nomads thus had a great advantage over the settled farmers and the cities and towns supported by the farmers.

D. Nomadic tribes are generally not amenable to large centrally administered political organizations; the most common type of organization is a loose tribal alliance under the leadership of a strong leader who comes from a strong and large tribe. With horses, the rate of intermingle among nomadic tribes increased greatly, enabling the nomadic peoples on the Eurasian steppes to have frequent changes in genetic and linguistic characteristics, belief systems and social customs. Of course, they also traded more frequently both with other nomadic groups and with the settled societies.

III. The North-South Rivalry

Nomadic and farming societies either traded or engaged in wars

A pattern: Across the Eurasian continent, the peoples along the East-West axis mostly traded; the peoples along the North-South axis often had confrontations. This was because the nomadic people in the north needed goods produced by the farming societies in the south and possessed the military means to take what they needed by force.

In addition to satisfying their own needs, the nomadic people also re-sold goods they obtained from one farming society to another farming society for profit.

D. The settled population often resorted to bribing the nomadic raiders to gain peace, generally with an amount which would make looting unattractive.

E. Some farming societies responded to the threat posed by the nomadic people by adopting the costumes and horse-back fighting techniques of the nomadic people and/or by constructing walls along the perimeter of defense to stop the mounted raiders. (King Wu-ling of Zhao during the Warring States Period in China did this in about 350 BCE.)

IV. Confrontations between Han and Xiong-Nu (Huni)

A. Xiong-Nu (often referred to in Europe as Huns) gained recognition around 400 B.C.E. in the Yinshan region in today’s Inner Mongolia, to the north of Hohhot, and became a threat to the settled Han people during the last years of the Warring States Period. They took advantage of the strife between Han and Chu following the demise of Qin Empire in late 3rd century B.C.E., threatening Han Dynasty in its first century.

B. The early Han emperors resort to marrying Han princesses to Xiong-Nu chiefs, but this did not give them lasting peace as Xiong-Nu often raided Han cities despite the peace treaties.

V. The Strategy of the Han Emperors

To launch military offensive against the Huns

To find allies in the Western Region against the Huns in order to cut off the supply lines of the Huns from the West

To acquire superior horses for the Han cavalry

VI. The Missions of Zhang Qian

First mission (138-127 BCE)

Second mission (116-114 BCE)

VII. The Impact of Zhang Qian’s Missions on the East-West Exchange

A. From China to the Western Regions

• Silk, metallurgy, Chinese medicinal herbs (including ginger)

• Chinese writing and administrative system

B. From Western Regions to China

• Horses, clover, walnut, cucumber, onion, garlic, etc.

• Buddhism, music, dance, acrobatics, etc.

VIII. The Impact of Zhang Qian’s Missions on the East-West Exchange

VIII. Relations between Han China and Egypt, Rome, Persia

A. With Ptolemaic Egypt

• Trade developed both through the Silk Road and the Sea Route

• Some Alexandrian merchants lived in Central China

• Many archeological finds show the extent of Chinese imports from Egypt (e.g., glassware)

B.With Roman Empire

• China and Rome learned the existence of each other during Han Dynasty;

• Silk was the main Chinese export and Rome was the largest importer;

• Glass utensils and decorative glass beads were imported to China, so was woolen material and amber.

C. With Parthian Persia

• Lute (pipa) and harp (konghou), two important music instruments in Chinese music, were both imported from Persia via Central Asia;

• Archeological finds include winged-beasts; documents mentioned that ostrich and lions from Africa came to China through Persia and Central Asia

• Some Buddhist monks of Persian origin came to China and introduced Buddhism to China

A. General Remarks

1. History is a function of geography; take China as an example

2. To understand history it is necessary to study not only the historical documents, which often record political events, military conflicts and diplomatic treaties, but also archeological findings, which provide material proof of the way a certain group lived. Historians also have to concern themselves with art and literature, linguistics and anthropology, trade and commerce, religious beliefs and social customs, technological development and economic conditions. Most importantly, it is necessary to examine the causality between different events and the circumstances that either strengthened or weakened the causality.

B. Consequences of Alexander’s Eastward Thrust

1. The Greeks in Bactria: Agents of East-West cultural exchange and fusion.

2.The Yue-chi (Tocharians):The exiles who became accidental conquerors and propagators of Buddhism to Central Asia and China.

II. The Use of Horses by Nomadic Peoples

Domestication of the horse gave the chariot and horse-riding warriors a huge advantage in battle. Shepherds on horseback could supervise much larger herds than on foot. Horse was until the train the fastest means of transport and communication.

Speed of the horse made long-distance trading easier.

The nomads thus had a great advantage over the settled farmers and the cities and towns supported by the farmers.

D. Nomadic tribes are generally not amenable to large centrally administered political organizations; the most common type of organization is a loose tribal alliance under the leadership of a strong leader who comes from a strong and large tribe. With horses, the rate of intermingle among nomadic tribes increased greatly, enabling the nomadic peoples on the Eurasian steppes to have frequent changes in genetic and linguistic characteristics, belief systems and social customs. Of course, they also traded more frequently both with other nomadic groups and with the settled societies.

III. The North-South Rivalry

Nomadic and farming societies either traded or engaged in wars

A pattern: Across the Eurasian continent, the peoples along the East-West axis mostly traded; the peoples along the North-South axis often had confrontations. This was because the nomadic people in the north needed goods produced by the farming societies in the south and possessed the military means to take what they needed by force.

In addition to satisfying their own needs, the nomadic people also re-sold goods they obtained from one farming society to another farming society for profit.

D. The settled population often resorted to bribing the nomadic raiders to gain peace, generally with an amount which would make looting unattractive.

E. Some farming societies responded to the threat posed by the nomadic people by adopting the costumes and horse-back fighting techniques of the nomadic people and/or by constructing walls along the perimeter of defense to stop the mounted raiders. (King Wu-ling of Zhao during the Warring States Period in China did this in about 350 BCE.)

IV. Confrontations between Han and Xiong-Nu (Huni)

A. Xiong-Nu (often referred to in Europe as Huns) gained recognition around 400 B.C.E. in the Yinshan region in today’s Inner Mongolia, to the north of Hohhot, and became a threat to the settled Han people during the last years of the Warring States Period. They took advantage of the strife between Han and Chu following the demise of Qin Empire in late 3rd century B.C.E., threatening Han Dynasty in its first century.

B. The early Han emperors resort to marrying Han princesses to Xiong-Nu chiefs, but this did not give them lasting peace as Xiong-Nu often raided Han cities despite the peace treaties.

V. The Strategy of the Han Emperors

To launch military offensive against the Huns

To find allies in the Western Region against the Huns in order to cut off the supply lines of the Huns from the West

To acquire superior horses for the Han cavalry

VI. The Missions of Zhang Qian

First mission (138-127 BCE)

Second mission (116-114 BCE)

VII. The Impact of Zhang Qian’s Missions on the East-West Exchange

A. From China to the Western Regions

• Silk, metallurgy, Chinese medicinal herbs (including ginger)

• Chinese writing and administrative system

B. From Western Regions to China

• Horses, clover, walnut, cucumber, onion, garlic, etc.

• Buddhism, music, dance, acrobatics, etc.

VIII. The Impact of Zhang Qian’s Missions on the East-West Exchange

VIII. Relations between Han China and Egypt, Rome, Persia

A. With Ptolemaic Egypt

• Trade developed both through the Silk Road and the Sea Route

• Some Alexandrian merchants lived in Central China

• Many archeological finds show the extent of Chinese imports from Egypt (e.g., glassware)

B.With Roman Empire

• China and Rome learned the existence of each other during Han Dynasty;

• Silk was the main Chinese export and Rome was the largest importer;

• Glass utensils and decorative glass beads were imported to China, so was woolen material and amber.

C. With Parthian Persia

• Lute (pipa) and harp (konghou), two important music instruments in Chinese music, were both imported from Persia via Central Asia;

• Archeological finds include winged-beasts; documents mentioned that ostrich and lions from Africa came to China through Persia and Central Asia

• Some Buddhist monks of Persian origin came to China and introduced Buddhism to China

HIST 48T/58L Updated Schedule

Lecture 1 (8 Oct 2009)

Alexander and his Eastern Thrust

Lecture 2 (15 Oct 2009)

Zhang Qian and the Opening of the Silk Road

Lecture 3 (22 Oct 2009)

Beauty of Loulan and the Tarim Basin During Han China

Lecture 4 (3 Nov 2009)

Buddhist Monks Bringing Scriptures to China (YD 106)

Lecture 5 (12 Nov 2009)

The Itinerant Sogdians

Lecture 6 (19 Nov 2009)

Battle of Talas – Midterm

Lecture 7 (24 Nov 2009)

Nestorians, Manicheans, Jews and Muslims in Tang & Song China (NH 202)

Lecture 8 (1 Dec 2009)

Mongol Rule

Lecture 9

Medieval Travelers

Lecture 10

The Timurids

Lecture 11

The Safavids and Uzbeks

Alexander and his Eastern Thrust

Lecture 2 (15 Oct 2009)

Zhang Qian and the Opening of the Silk Road

Lecture 3 (22 Oct 2009)

Beauty of Loulan and the Tarim Basin During Han China

Lecture 4 (3 Nov 2009)

Buddhist Monks Bringing Scriptures to China (YD 106)

Lecture 5 (12 Nov 2009)

The Itinerant Sogdians

Lecture 6 (19 Nov 2009)

Battle of Talas – Midterm

Lecture 7 (24 Nov 2009)

Nestorians, Manicheans, Jews and Muslims in Tang & Song China (NH 202)

Lecture 8 (1 Dec 2009)

Mongol Rule

Lecture 9

Medieval Travelers

Lecture 10

The Timurids

Lecture 11

The Safavids and Uzbeks

Sunday, October 25, 2009

LECTURE 3 / 22 OCTOBER 2009

Beauty of Loulan and the Tarim Basin During Han China

I. Geography of the Western Regions

• Hexi Corridor

• Junggar Basin (between Altay Mountain and Tian Shan)

• Tarim Basin (between Tian Shan and Kunlun Mountain; Taklamakan Desert and the oases)

• Ili River (emptying into Lake Balkash)

• Fergana Valley (north of the Pamir Plateau)

• Transaxiana (east of the Aral Sea; between Syr Darya and Amu Darya)

II. After Zhang Qian’s Missions

• Han China seized the initiative and forced Xiong-nu to split into two groups.

• One group moved south and integrated in the Han population.

• The main body of Xiong-nu fled westward, displacing peoples on their way, driving some of them further west, ultimately causing Germanic tribes to invade Roman territories in Western Europe.

III. Early Settlers in Tarim Basin

Tocharians

• Tocharians (a term given by European scholars) moved into Junggar Basin before 2000 BCE; Indo-Europeans who spoke a western dialect, akin to the languages spoken by Celts, Hittites and Greeks.

• By contrast, Persians and Aryans who invaded India around 1500 BCE spoke an eastern Indo-European dialect (even though they were located to the west of the Tocharians), .

• Credited with bringing wheat to East Asia.

B. Scythians (Sakas)

• Scythians spoke an Iranian language, were an early group of Indo-Europeans who wandered on the Eurosian steppes. .

• Some migrated south and became settled farmers; the majority practiced pastoralism.

• They were known as Scythians, Sakas and Saizhong, by ancient Greeks, Persians and Chinese.

• First to domesticate the horse and to fight on the horseback.

REMARK: Tocharians and Scythians were the early settlers in Junggar and Tarim basins.

The Yue-Chi’s

• Yue-Chi’s were a Tocharian group which populated the Hexi Corridor, Qaidam basin and Junggar basin.

• They interacted with the Qiang group, speakers of a Sino-Tibetan language and related to Tibetans.

• Yue-Chi’s were driven out of Hexi Corridor by Xiong-nu and moved successively to the Ili River area, the Fergana Valley, Transaxiana, Bactria and Gandhara.

• A sub-group of Yue-Chi had populated the eastern part of the Tarim basin when Xiong-nu became powerful in the Western Regions.

IV. Hexi Corridor and the Oases States in Today’s Xinjiang During West Han

A. Administrative measures by Han dynasty

• Along the 1200 km Hexi Corridor, Han set up four counties with four garrison towns which were also centers of trade and cultural exchange.

• This administrative structure has remained for more than 2000 years.

• Han dynasty also extended its power in the Junggar and Tarim basins, stationed soldiers in key locations and constructed walls and beacon towers throughout the region.

• Han took Loulan in the east and Fergana in the west by force and established suzerainty throughout the Western Region, requiring each state to send a prince to Chang’an as a guarantee of its allegiance to Han.

• Since Xiong-nu was no longer a major player in the region, and since trade flourished between Han and these states, most of the oases states were under Han domination.

• Rebellion sometimes broke out, usually when there was internal turmoil in China proper.

V. Ban Chao and His Exploits

• Ban Chao (32-102 CE), from a prominent family, chose to be a soldier rather than a court official; he was sent to the Western Regions in 73 CE as the leader of a 36-man elite force.

• This elite force took daring and decisive actions in subduing adversaries and showed diplomatic skills in dealing with the various states on the oases in the Tarim Basin.

• Ban Chao subsequently worked to fend off occasional incursions of Xiong-nu and Yue-chi into these states, enforcing Han’s control over the Western Region and ensuring passage of the trade routes.

• In 97 EC, he sent an associate, Gan Ying, to visit the Roman Empire, but Gan Ying only reached the Persian Gulf. His report was interesting and useful.

• After serving in the Western Regions for nearly 30 years, Ban Chao pleaded with the emperor to allow him to return. But his plea was ignored.

• After his sister risked her own life to plea on his behalf, he was finally allowed to return home and died shortly after.

• Later his son Ban Yong was appointed to the same post and made further gains for Han Dynasty.

• It was about this period that Buddhism came to central China from the Tarim Basin.

VI. Loulan Kingdom

• Loulan was the eastern-most oasis state among dozens of small states ringing the Tarim Basin. Travelers from China proper must rest in Loulan before going forward.

• Its strategic location made it a center of commerce and a meeting point of different cultures.

• Due to shifting and drying of the river near it, Loulan became submerged under the sand around 1200 CE.

• However, many earlier Chinese poems made references to Loulan in romantic terms.

• The British archeologist Stein made two expeditions in early 20th century into the Lop Nor area and discovered the Loulan site, taking away many documents written in different languages, including Tocharian, Chinese and Khotan.

• Because of its geo-political importance, also due to the reputed beauty of Loulan girls, many rulers of the Tarim states took Loulan women as wives.

• Chinese archeologists found toward the end of 20th century many more artifacts at the Loulan site which demonstrate the multi-cultural character of Loulan as well as its close relationship with China proper.

VII. Shule Kingdom

• On a large oasis at the western edge of the Tarim Basin, with Fergana Valley lying just to the northwest of the Pamirs .

• Important to Han’s position in the Western Region, hence there were Han soldiers and civilians in Shule to ensure its allegiance.

• Sometimes under Xiong-nu threat but never conquered by them.

• Later known as Kashgar, always under the cultural influences of Persia, India and China

VIII. Yutian (Khotan) Kingdom

• At the southern edge of the Tarim Basin, just north of Kunlun Mountain

• Rich in high-quality jade and an important supplier to China for over 4000 years

• Residents were descendents of Scythians, with some Qiang elements

• Close-ties with Han and a major conduit by which Buddhism entered China

IX. Niya Kingdom

• Recorded in Chinese history books in detail, but no trace of it in recent centuries

• Stein made efforts to unearth it without success

• In 1994, a combined Chinese-Japanese team discovered its precise site and made extensive investigations

• Many treasures were found, among which is an embroidered elbow pad with Chinese characters and animals or legendary animals of Persia and Africa

I. Geography of the Western Regions

• Hexi Corridor

• Junggar Basin (between Altay Mountain and Tian Shan)

• Tarim Basin (between Tian Shan and Kunlun Mountain; Taklamakan Desert and the oases)

• Ili River (emptying into Lake Balkash)

• Fergana Valley (north of the Pamir Plateau)

• Transaxiana (east of the Aral Sea; between Syr Darya and Amu Darya)

II. After Zhang Qian’s Missions

• Han China seized the initiative and forced Xiong-nu to split into two groups.

• One group moved south and integrated in the Han population.

• The main body of Xiong-nu fled westward, displacing peoples on their way, driving some of them further west, ultimately causing Germanic tribes to invade Roman territories in Western Europe.

III. Early Settlers in Tarim Basin

Tocharians

• Tocharians (a term given by European scholars) moved into Junggar Basin before 2000 BCE; Indo-Europeans who spoke a western dialect, akin to the languages spoken by Celts, Hittites and Greeks.

• By contrast, Persians and Aryans who invaded India around 1500 BCE spoke an eastern Indo-European dialect (even though they were located to the west of the Tocharians), .

• Credited with bringing wheat to East Asia.

B. Scythians (Sakas)

• Scythians spoke an Iranian language, were an early group of Indo-Europeans who wandered on the Eurosian steppes. .

• Some migrated south and became settled farmers; the majority practiced pastoralism.

• They were known as Scythians, Sakas and Saizhong, by ancient Greeks, Persians and Chinese.

• First to domesticate the horse and to fight on the horseback.

REMARK: Tocharians and Scythians were the early settlers in Junggar and Tarim basins.

The Yue-Chi’s

• Yue-Chi’s were a Tocharian group which populated the Hexi Corridor, Qaidam basin and Junggar basin.

• They interacted with the Qiang group, speakers of a Sino-Tibetan language and related to Tibetans.

• Yue-Chi’s were driven out of Hexi Corridor by Xiong-nu and moved successively to the Ili River area, the Fergana Valley, Transaxiana, Bactria and Gandhara.

• A sub-group of Yue-Chi had populated the eastern part of the Tarim basin when Xiong-nu became powerful in the Western Regions.

IV. Hexi Corridor and the Oases States in Today’s Xinjiang During West Han

A. Administrative measures by Han dynasty

• Along the 1200 km Hexi Corridor, Han set up four counties with four garrison towns which were also centers of trade and cultural exchange.

• This administrative structure has remained for more than 2000 years.

• Han dynasty also extended its power in the Junggar and Tarim basins, stationed soldiers in key locations and constructed walls and beacon towers throughout the region.

• Han took Loulan in the east and Fergana in the west by force and established suzerainty throughout the Western Region, requiring each state to send a prince to Chang’an as a guarantee of its allegiance to Han.

• Since Xiong-nu was no longer a major player in the region, and since trade flourished between Han and these states, most of the oases states were under Han domination.

• Rebellion sometimes broke out, usually when there was internal turmoil in China proper.

V. Ban Chao and His Exploits

• Ban Chao (32-102 CE), from a prominent family, chose to be a soldier rather than a court official; he was sent to the Western Regions in 73 CE as the leader of a 36-man elite force.

• This elite force took daring and decisive actions in subduing adversaries and showed diplomatic skills in dealing with the various states on the oases in the Tarim Basin.

• Ban Chao subsequently worked to fend off occasional incursions of Xiong-nu and Yue-chi into these states, enforcing Han’s control over the Western Region and ensuring passage of the trade routes.

• In 97 EC, he sent an associate, Gan Ying, to visit the Roman Empire, but Gan Ying only reached the Persian Gulf. His report was interesting and useful.

• After serving in the Western Regions for nearly 30 years, Ban Chao pleaded with the emperor to allow him to return. But his plea was ignored.

• After his sister risked her own life to plea on his behalf, he was finally allowed to return home and died shortly after.

• Later his son Ban Yong was appointed to the same post and made further gains for Han Dynasty.

• It was about this period that Buddhism came to central China from the Tarim Basin.

VI. Loulan Kingdom

• Loulan was the eastern-most oasis state among dozens of small states ringing the Tarim Basin. Travelers from China proper must rest in Loulan before going forward.

• Its strategic location made it a center of commerce and a meeting point of different cultures.

• Due to shifting and drying of the river near it, Loulan became submerged under the sand around 1200 CE.

• However, many earlier Chinese poems made references to Loulan in romantic terms.

• The British archeologist Stein made two expeditions in early 20th century into the Lop Nor area and discovered the Loulan site, taking away many documents written in different languages, including Tocharian, Chinese and Khotan.

• Because of its geo-political importance, also due to the reputed beauty of Loulan girls, many rulers of the Tarim states took Loulan women as wives.

• Chinese archeologists found toward the end of 20th century many more artifacts at the Loulan site which demonstrate the multi-cultural character of Loulan as well as its close relationship with China proper.

VII. Shule Kingdom

• On a large oasis at the western edge of the Tarim Basin, with Fergana Valley lying just to the northwest of the Pamirs .

• Important to Han’s position in the Western Region, hence there were Han soldiers and civilians in Shule to ensure its allegiance.

• Sometimes under Xiong-nu threat but never conquered by them.

• Later known as Kashgar, always under the cultural influences of Persia, India and China

VIII. Yutian (Khotan) Kingdom

• At the southern edge of the Tarim Basin, just north of Kunlun Mountain

• Rich in high-quality jade and an important supplier to China for over 4000 years

• Residents were descendents of Scythians, with some Qiang elements

• Close-ties with Han and a major conduit by which Buddhism entered China

IX. Niya Kingdom

• Recorded in Chinese history books in detail, but no trace of it in recent centuries

• Stein made efforts to unearth it without success

• In 1994, a combined Chinese-Japanese team discovered its precise site and made extensive investigations

• Many treasures were found, among which is an embroidered elbow pad with Chinese characters and animals or legendary animals of Persia and Africa

Thursday, October 15, 2009

READINGS

Maps - PDF at Hisar Copy Center

"China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization" at Hisar Copy Center

“The History and Civilization of China” - PDF at Hisar Copy Center

“World Civilizations: The Global Experience”, Peter N. Stearns - Library Online Course Reserve - Course Code HIST 105

“Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past”, Jerry Bently and Herbert Ziegler - PDF at Hisar Copy Center

"China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization" at Hisar Copy Center

“The History and Civilization of China” - PDF at Hisar Copy Center

“World Civilizations: The Global Experience”, Peter N. Stearns - Library Online Course Reserve - Course Code HIST 105

“Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past”, Jerry Bently and Herbert Ziegler - PDF at Hisar Copy Center

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

LECTURE 1 / 8 OCTOBER 2009

Overall Perspective

A. The Eurasian Continent

•The Eurasian continent is a contiguous landmass comprising some 55 million square kilometers or 3/5 of the total land area of the earth.

•A line drawn from the northeast corner of the Eurasian continent (northern part of Kamchatka Peninsula) southwestward to the southwest part of Arabian Peninsula (Aden) divides the landmass into two triangles.

•The lower triangle is warm and humid, with an annual precipitation of over 500 mm; this area contains some of the best agricultural zones of the world.

•The base of the upper triangle is generally dry and consists mostly of steppes and deserts; this area is mostly for herding or animal husbandry.

•North to the steppes are vast areas of coniferous forest; this area is mostly for hunting.

B. Comparison of the Eurasian Continent with the Americas, Africa and Australia

•Very large land areas spreading over mild weather zones of roughly similar weather patterns. Easier to communicate between East and West than between North and South.

•The availability of large animals that can be domesticated.

C. Routes of Exchanges Across the Continent

•East-West Exchanges: To the north, a “steppe route” used by the nomadic peoples; to the south, a “sea route” used by the coastal seafarers; in the middle, an “oasis route”, used by the agricultural peoples.

•North-South Exchanges: Orhon River to Chang’an, a main trade route between the nomadic tribes and the farming people along the Yellow River; from Tibet to the Tarim Basin and further north to the Junggar Basin; from Central Asia down to Afghanistan and then to India; from the eastern coast of the Mediterranean to Anatolia, Astrakhan etc.; Constantinople (Istanbul) south to the Mediterranean and Egypt and north to the Black Sea, thus East and North Europe.

•These networks of communications have allowed from very ancient times the exchanges of goods, social practices and ideas.

D. Means and Effects of Exchange

•Exchange among different groups are natural in human experience. These contacts have resulted in racial and cultural integration for the most part. The exchanges sometimes take the form of war, but mostly through peaceful means.

•However, wars have been effective catalysts for cultural adaptation and integration.

•The peoples in the East first developed a very sophisticated civilization, including technologies, sciences, social institutions and writing systems; these were adopted and integrated by the Greeks in the West.

•Alexander the Great was a product and a symbol of the Greek civilization; his expedition to the East brought a further integration and fusion of these two types of culture. Philip II (382–336 B.C.E.) of Macedonia unified Greece and decided to conquer the East. His son Alexander continued his unfulfilled ambition by leading a Greek-Macedonian army to the East.

I. Persian Empire

II. Classical Greece

III. Wars between Persia and Greece

IV. Alexander the Great and His Eastern Thrust

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic World

Ptolemy’s Rule of Egypt

* Ptolemaic Dynasty

* Ptolemy’s Support for Culture

* Seleucus Ruled the Asian Territories

Economy and Culture of the Hellenistic Period

Four major cities of the Hellenistic Period

Alexanderia

•Built by Alexander in 332 BCE.

•Becoming an important city in the world and a center of Greek culture within 100 years.

Pergamum

•Capital of Attalid kingdom.

•One of the most important and beautiful cities in the Hellenistic period.

•The Pergamum library was next only to the Alexanderia library in size and importance.

Antioch

•Established by Seleucus I in 330 BCE

•It was the western terminal point of trade from Asia to the Mediterrenean region.

•The third largest city (next to Rome and Alexanderia) of the Roman Empire, with temples, theaters, aquaducts and public baths.

Athens

•Declining in importance during the Hellenistic period, Athens often needed financial support from the other rulers.

•Rulers of the Ptolemaic dynasty donated a statium next to the Theseus Temple.

•The Ptolemaic rulers offered their favorite god Isis in the temple in Athens.

•Athens remained a center for philosophy and culture along with Alexandria.

Trade Networks

•The Mediterrenean was joined with Indian Ocean

•India and East Africa were connected by ships following the mansoons

•Roads connected Asia Minor, Central Asia and India

•The central governments of each region maintained the roads with military garrisons to allow the merchants safe passage as well as to levy the trade taxes.

•“The Silk Road” began to take shape

•The main trading cities were Taxila, Bukhara, Merv, Palmyra, Antioch, Tyre, Alexandria, etc.

V. The Influence of Alexander’s Eastern Thrust

•There are estimated some 80 cities which were named Alexandria in today’s West and Central Asia.

•Many legends in the Persian speaking world are based on Alexander, corrupted to be Iskander and glorified in many literary works, e.g., Shahname by Firdausi (Firdevsi).

A. The Nature of Hellenistic Culture

•The Hellenistic culture in essence was a fusion of the Greek culture and the Asian cultures of the regions conquered by Alexander.

•Alexander was convinced that the Eastern peoples were not barbaric as Aristotle had taught him but cultured in their own way; he sought to fuse the two cultures by encouraging racial and cultural integration. For example, he married two Asian wives and began to wear Persian costumes. He also encouraged 9,000 Greek soldiers to take Perisan wives at a large wedding ceremony.

B.Bactria and Gandhara Culture

•Greek Rulers of Bactria

•Bactria was in today’s Afghanistan near Pakistan. The Greek generals who ruled this area became independent of the Seleucid rulers based in Damascus in 2nd century BCE.

•Buddhism which began in India was introduced to this area around this time.

•A majority of the Greek population in Bactria adopted Buddhism.

•Gandhara Art

•Buddhists in India originally did not images of Buddha, believing that it was impossible to portray him.

•However, the Buddhists in Bactria felt a need to worship Buddha with the human image. Hence, they applied the Greek sculpture and painting techniques to Buddha and other deities.

•This was the possible because Bactria was far away from the center of Buddhism.

•The Spread of Gandhara Art

•The Gandhara art spread to Central Asia and from there to China; it also propagated to Southeast Asia via the sea route.

•Exchange and fusion of different cultures have always existed; the appearance and spread of the Gandhara art is a case which can be clearly traced to its origin with documentary evidence and archeological findings.

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

HIST 48T Syllabus

Course on “China and the Silk Road” by H. K. Chang

Three routes have been connecting the east and west parts of Eurasia. In the north in ancient times, the nomadic peoples transferred goods, technologies and ideas across the Eurasian steppes. In the south, the sea-faring peoples along the coasts of China, East and Southeast Asia, India and South Arabia have created a sea route that carried people, goods as well as customs and ideas. Between the steppes and the sea routes, in a mostly arid zone, there is a network of land routes strung together by many oases and across many mountain passes. This is known as the Silk Road. It can be narrowly defined as a 10,000 km route that begins in Xi’an (or Chang’an) and ends in Istanbul (Constantinople).

The Silk Road was the most effective route of communication from 3rd century B.C.E. to 16th century C.E. Its importance declined drastically after the Europeans reached Asia by sea, thus dominating world commerce.

With energy issues and cultural-political conflicts being a focus of international attention, the Silk Road has regained its previous importance. With China re-emerging on the world stage, its historical connections to the western part of Eurasia should be of not only academic but also practical interest.

Course Outline

This course surveys China’s role in the Silk Road from the expeditions of Alexander the Great, through the medieval times of Mongol rule, down to the Russo-British rivalry in Central Asia in the 19th century. Important cultural as well as economic exchanges are emphasized.

It consists of twelve 2-period lectures followed by a 1-period discussion as follows:

Lecture 1 Alexander’s Eastward Thrust and the Buddhist Art

Lecture 2 Zhang Qian and Opening of the Silk Road

Lecture 3 Beauty of Loulan and the Tarim Basin During Han China

Lecture 4 Buddhist Monks on the Silk Road: Bringing Scriptures to China

Lecture 5 From Samarkand to Chang’an: The Itinerant Sogdians

Lecture 6 Battle of Talas: Turning-Point in Tang Influence

Lecture 7 Nestorians, Manicheans, Jews and Muslims in Tang and Sung China

Lecture 8 Mongol Rule: From Terror and Destruction to Law and Order

Lecture 9 Medieval Travelers: Marco Polo, Ibn Battutah and Wang Dayuan

Lecture 10 The Timurids: Turco-Persian Cultural Florescence

Lecture 11 Shah Ismail and Muhammad Shaybani: Facing the Changing Tide

Lecture 12 Bukhara, Khiva and Khoqand: Sunset on the Silk Road

Course Material and Lectures

Graphical PowerPoint presentations with photo images will be the format of all lectures. The PowerPoint plus the assigned reading material will be mounted on a specially created course blog within 48 hours of each lecture.

Examinations and Grading

Students will be tested at the mid-term and final examinations on their familiarity and understanding of the material presented in the class.

In addition, each student is required to submit a term paper of about 2000 words based on a title and a bibliography pre-approved by the professor.

Grades will be assigned on the basis of three components: the mid-term exam weighing 35%, the final exam weighing 35% and the term-paper weighing 30%.

Three routes have been connecting the east and west parts of Eurasia. In the north in ancient times, the nomadic peoples transferred goods, technologies and ideas across the Eurasian steppes. In the south, the sea-faring peoples along the coasts of China, East and Southeast Asia, India and South Arabia have created a sea route that carried people, goods as well as customs and ideas. Between the steppes and the sea routes, in a mostly arid zone, there is a network of land routes strung together by many oases and across many mountain passes. This is known as the Silk Road. It can be narrowly defined as a 10,000 km route that begins in Xi’an (or Chang’an) and ends in Istanbul (Constantinople).

The Silk Road was the most effective route of communication from 3rd century B.C.E. to 16th century C.E. Its importance declined drastically after the Europeans reached Asia by sea, thus dominating world commerce.

With energy issues and cultural-political conflicts being a focus of international attention, the Silk Road has regained its previous importance. With China re-emerging on the world stage, its historical connections to the western part of Eurasia should be of not only academic but also practical interest.

Course Outline

This course surveys China’s role in the Silk Road from the expeditions of Alexander the Great, through the medieval times of Mongol rule, down to the Russo-British rivalry in Central Asia in the 19th century. Important cultural as well as economic exchanges are emphasized.

It consists of twelve 2-period lectures followed by a 1-period discussion as follows:

Lecture 1 Alexander’s Eastward Thrust and the Buddhist Art

Lecture 2 Zhang Qian and Opening of the Silk Road

Lecture 3 Beauty of Loulan and the Tarim Basin During Han China

Lecture 4 Buddhist Monks on the Silk Road: Bringing Scriptures to China

Lecture 5 From Samarkand to Chang’an: The Itinerant Sogdians

Lecture 6 Battle of Talas: Turning-Point in Tang Influence

Lecture 7 Nestorians, Manicheans, Jews and Muslims in Tang and Sung China

Lecture 8 Mongol Rule: From Terror and Destruction to Law and Order

Lecture 9 Medieval Travelers: Marco Polo, Ibn Battutah and Wang Dayuan

Lecture 10 The Timurids: Turco-Persian Cultural Florescence

Lecture 11 Shah Ismail and Muhammad Shaybani: Facing the Changing Tide

Lecture 12 Bukhara, Khiva and Khoqand: Sunset on the Silk Road

Course Material and Lectures

Graphical PowerPoint presentations with photo images will be the format of all lectures. The PowerPoint plus the assigned reading material will be mounted on a specially created course blog within 48 hours of each lecture.

Examinations and Grading

Students will be tested at the mid-term and final examinations on their familiarity and understanding of the material presented in the class.

In addition, each student is required to submit a term paper of about 2000 words based on a title and a bibliography pre-approved by the professor.

Grades will be assigned on the basis of three components: the mid-term exam weighing 35%, the final exam weighing 35% and the term-paper weighing 30%.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)