Stearns - Chapters 4, 5, 17

China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization - Chapters 3, 18, 19, 21

Encounters - Chapters 4, 9, 11, 14

The History and Civilization of China - pp. 1-108

Two articles and a map at Hisar Copy Center under the course name

Saturday, November 14, 2009

LECTURE 5 / 12 NOVEMBER 2009

From Samarkand to Chang’an: The Itinerant Sogdians

I. The Ancient Sogdian Letters

I. The Ancient Sogdian LettersIn 1907, under a Han dynasty watchtower northwest of Dunhuang, the Hungarian-British Archeologist Aurel Stein found a mail bag containing 8 letters written in the Sogdian language; 3 of them were too fragmented to read but 5 were relatively intact

B. Stein turned these letters to the British Museum; experts in the Museum and other experts began to try to translate them

C. After several trials and improvements over the past 100 years, we now know the complete content of these 5 letters

D. They were written by Sogdian merchants in 312 CE to other Sogdian merchants on the Silk Road or to their families in Samarkand

II. Who Were the Sogdians?

Sogdians were farming and trading people who lived in the Zarafshan River Valley in today’s Uzbekistan and spoke an Eastern Iranian language

They were ruled by Archamenids from Persia in 5th century BCE, Alexander (and the Seleucid Greek kingdom), and the Kushans.

Even though the Sogdians never had a united and strong kingdom of their own, they were very visible in Central Asia throughout its history.

III. The Rise of Sogdian Merchants on the Silk Road and Elsewhere

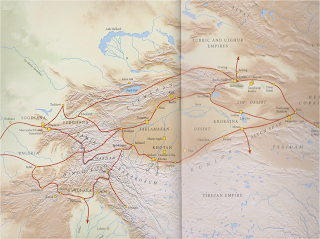

From 3rd to 10th century CE the dominant traders on the Silk Road were the Sogdians whose reach encompassed the Byzantine Empire, India and China.

Before the rise of Sogdians, Indians and Persians were prominent in the trade in Eurasia.

This may have been caused by the disruptions brought by Xiongnu’s westward and southward thrust, creating a vacuum for the Sogdians to fill in the central region of the Eurasian continent.

Therefore, not only were the Sogdians prominent in trade with China, but they were also active in South Asia and West Asia

IV. The Master Traders on the Silk Road

The ancient Sogdian letters give clear evidence that trade along the Silk Road mostly took place between Sogdian merchants some of whom were resident in various countries.

Since the Sogdians did not have their own currency, the common medium for trade was the Sassanian gold coins until the 7th century when Tang Chinese coins became the common currency in trade on the Silk Road.

Sogdian merchants brought spices, glassware, jewelry, medicinal material from the West to the East; they brought silk, tea and lacquerware.

They also traded rare animals, slaves, even singers, dancers and acrobats.

V. Sogdian Communities Along the Silk Road and in Eastern China

As trade developed, many Sogdians chose to stay in trading centers, forming their own community and having their own governing system as well as religious institutions (mainly Zoroastrian temples).

Historical records and archeological findings indicate at least 30 such communities from Kashgar in the west end of today’s China to Liaoning province in the northeast.

The leader of a Sogdian trade caravan was called a Sartpaw; the community leader of resident Sogdians was known by the same title.

This quasi autonomous communities often had their own armed forces, religious clergy and other administrative arrangements including the community coffer.

VI. The Integration of Sogdian Communities in the Chinese Society

The Sogdians were identified in Chinese historical records and other documents in the 3rd century.

Sogdians were also recruited into the army and often served in the imperial palace.

Almost all of the Sogdians who stayed in China took one of nine of the existing Chinese surnames; therefore, they were also known in China as a group of people with these nine surnames (“zhao-wu jiu-xing”).

During Tang dynasty, the Sogdians were known as good musicians and dancers; many of the roughly 3000 wine shops in Chang’an were run and staffed by Sogdians.

E. The central Chinese governments began to appoint the Sogdian community leaders as local officials with the title “Sabao”, the Sinicized version of Sartpaw.

F. During Sui and Tang periods, these Sogdian communities were integrated into the local administrative structure as regular “Xiang’s” or “Li’s”. (乡里)

G. Those Sogdian families who stayed in China long enough gradually became indistinguishable from the other Chinese.

VII. Contributions of the Sogdians to China

In addition to music and dance, the Sogdian clothing style became fashionable during the Tang dynasty.

Some rare animals from Africa and other places were introduced by Sogdians.

Sogdians brought their religious practices as well as artifacts which were merged in Chinese Buddhism.

The Sogdian script was later borrowed by the Uyghurs, Mongols and Manchus successively in their own writing system.

The Sogdian merchants greatly enhanced Chinese economy, enriching the material life in China.

Sogdians were mainly or at least partially responsible for the introduction of Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, and Nestorian Christian faith in China.

VIII. The Most Infamous Sogdian in Chinese History

An Lu Shan (Roxan) was born in China of Sogdian parentage; he became a regional military commander in northeast China.

During the reign of Tang Xuan Zong An Lu Shan, though very trusted by the emperor, started a rebellion which nearly toppled the Tang dynasty and caused decline of Tang power from the point onward.

His rebellion was defeated by the Tang forces with help from the Arabs and Uyghurs.

An Lu Shan has since been a household name in China, in a negative sense.

LECTURE 4 / 3 NOVEMBER 2009

I. Two Examples of Revisionist History

A. An Early Christian Community in China [by HKC]

Ban Chao dispatched his associate Gan Ying to visit Roman Empire (97 CE); Gan reached the Persian Gulf but was told by the Persians that it was too dangerous to cross the turbulent sea; therefore, he returned without getting to the Roman Empire

A. An Early Christian Community in China [by HKC]

Ban Chao dispatched his associate Gan Ying to visit Roman Empire (97 CE); Gan reached the Persian Gulf but was told by the Persians that it was too dangerous to cross the turbulent sea; therefore, he returned without getting to the Roman Empire

B. Reason for Zhang Qian’s Mission

Grotto Painting in Dunhuang done in 4th century

Depicting the scene of Zhang Qian departing China with Emperor Wu bidding him farewell

Han army captured a huge statue, “Golden Man”, from Xiongnu who worshipped it because it was a statue of Buddha from the West

Therefore Emperor Wu sent Zhang Qian to the West in order to learn more about Buddha

Since Buddhism was the dominant religion in Central Asia and India at the time of Zhang Qing’s mission and since Zhang Qian was inquisitive about the region, e.g., commerce between Bactria and India, it was possible that Zhang Qian learned about Buddhism and reported this to the Emperor; but this was not recorded in the official history on his mission

At any rate, Zhang Qian could only have learned of Buddhism after he arrived in the Western Region

Buddhists did not make or worship statues of Buddha until the Kushan Period which began more than 100 years after Zhang Qian’s death

II. Monks from the West to China

A. Parthamasiris (c. 100 CE)

Prince of Parthian Persia, lost to his uncle in the succession and took the throne of Armenia; when Romans conquered Armenia, they proposed Parthamasris to be King of Parthian Persia.

Objections from the Persians forced him to seek solace as a monk in Buddhism

He was an erudite man and able to achieve a high-level understanding and interpretation of Theraveda (Hinayana) Buddhism

Coming to China c. 140 CE, he mastered the Chinese language in just a few years

In charge of translating Theraveda scriptures for 23 years (148-171 CE) and starting a new style of Chinese prose

Taking refuge in southern China during the turmoil at the end of Han Dynasty and died there

B. Lokaksin

A Yue-chi, arriving in the Han capital toward the end of Han Dynasty

Translated scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism for over 10 years (178-189 CE)

Disappeared from public view after this work

C. Kumarajiva (344∼413 C.E.)

Father was an Indian noble, mother was a princess of Qiuci (Kucha)

Followed his mother to a nunery at age 7

Became learned at a young age; well versed in Theraveda Buddhism and gained a wide reputation not only in Central Asia but also in China

After he declined to come to Chang’an to serve a ruler at the time, he was forcibly taken to inside the Chinese border by the ruler’s army (382 CE) and stayed 18 years near the border even after the ruler himself was disposed

In 401 CE he was taken to Chang’an by a new ruler and provided with a team of 120 Chinese monks to assist him in translating the Mahayana Buddhist works

Over 600 volumes were completed during his time

He was credited for a new method of translation which is relevant even today

Founded a new school of Buddhist philosophy which resulted in a new sect

Admired as a genius, he was “ordered’ by the ruler to marry ten maidens so that his talent can be inherited

III. Chinese Monks to the West

A. Zhu Shiheng (c. 250 CE)

First Chinese monk to go west in search of true Buddhist scriptures

Confused about the Buddhist literature’s correctness and authenticity, went to Khotan (Yu-tian) to learn more

Obtained 90 volumes and sent them back to Luoyang after overcoming difficulties

Died in Khotan at age 80

B. Fa Hsian (Fa Xian)

Born in 334 and died in 420 C.E.

Decided to become a monk when his parents both died

First Chinese monk to go to India

He was 60 when he started his long journey in the company of 10 Chinese monks

Took 6 years to reach Central India, stayed there for 6 years to learn the language and the scriptures, 2 years in the south, including today’s Sri Lanka, and 1 year to return home by sea

Wrote “Buddist-Country Records” after his return, detailing his experiences

A compendium of Buddhist temples, practices, geography and history of Central Asia and Indian

C. Sung Yun

A native of Dunhuang, worked in the capital city of Luoyang in early 6th century

Was sent by the Empress Dowager of the ruling dynasty to the West to present gifts and seek better scriptures (518 CE)

Reached Khotan and the Pamirs by passing through many small states

IV. The Story of Xuan Zang

Born (602 CE) into a family of intellectuals and officials

Entered monastery at 13 and became a ordained monk at 21

Spending five years visiting many Buddhist scholars and learned major classical Buddhist works

Puzzled by differences in these works regarding the ways to reach nirvana, decided to seek truth from India despite the dangers and difficulties involved

Upon return he was offered a ministerial post but declined; was given resources by the Emperor to translate the books he brought back

His style was much more fluid and elegant than the previous translators

But he was far more than a translator of Buddhist scriptures

He compiled, with the help of his disciple, a book on the West at the request of the Tang Emperor and gave vivid and detailed accounts of some 138 states he had visited

He was also the founder of the new Buddhist school based on the new philosophy he had helped to form while in India

The Great Tang’s Records of the Western World (Ta-Tang-Si-Yu-Ki)

On Xuan Zang’s Return to Chang’an

Xuan Zang stated that he saw this and described its precise location

Archeological work was done in early 20 century to uncover it

Asoka’s Pillar near the birthplace of Buddha

Erected around 300BCE; excavated around 1910

V. Impact of Buddhism in China

Introduced into China in the turbulent times in Chinese history; gained acceptance and grew in influence during the 400 years of turmoil in northern China

Buddhism, along with Taoism, provided comfort and a hope of after-life to people who suffered

Many rulers of the northern regimes were non-Han; they needed a form of worship that was different from Confucianism and Taoism

As a result, Buddhism took Chinese a characteristic; Theraveda which focused more on the individual was overlooked, Mahayana which emphasized helping others to achieve nirvana become the standard Buddhism in China, hence, Korea, Japan and Vietnam

Buddhist and Chinese philosophy influenced each other, resulting in transformation of both; in terms of Buddhism, it was the Zen school of Buddhism

VI. Between Body and Soul

Biological being and social being

Instinctive being, intellectual being and emotive being

Religion of salvation and religion of transcendental meditation

For discussion: What motivated the early Buddhist monks and what gave them strength?

Depicting the scene of Zhang Qian departing China with Emperor Wu bidding him farewell

Han army captured a huge statue, “Golden Man”, from Xiongnu who worshipped it because it was a statue of Buddha from the West

Therefore Emperor Wu sent Zhang Qian to the West in order to learn more about Buddha

Since Buddhism was the dominant religion in Central Asia and India at the time of Zhang Qing’s mission and since Zhang Qian was inquisitive about the region, e.g., commerce between Bactria and India, it was possible that Zhang Qian learned about Buddhism and reported this to the Emperor; but this was not recorded in the official history on his mission

At any rate, Zhang Qian could only have learned of Buddhism after he arrived in the Western Region

Buddhists did not make or worship statues of Buddha until the Kushan Period which began more than 100 years after Zhang Qian’s death

II. Monks from the West to China

A. Parthamasiris (c. 100 CE)

Prince of Parthian Persia, lost to his uncle in the succession and took the throne of Armenia; when Romans conquered Armenia, they proposed Parthamasris to be King of Parthian Persia.

Objections from the Persians forced him to seek solace as a monk in Buddhism

He was an erudite man and able to achieve a high-level understanding and interpretation of Theraveda (Hinayana) Buddhism

Coming to China c. 140 CE, he mastered the Chinese language in just a few years

In charge of translating Theraveda scriptures for 23 years (148-171 CE) and starting a new style of Chinese prose

Taking refuge in southern China during the turmoil at the end of Han Dynasty and died there

B. Lokaksin

A Yue-chi, arriving in the Han capital toward the end of Han Dynasty

Translated scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism for over 10 years (178-189 CE)

Disappeared from public view after this work

C. Kumarajiva (344∼413 C.E.)

Father was an Indian noble, mother was a princess of Qiuci (Kucha)

Followed his mother to a nunery at age 7

Became learned at a young age; well versed in Theraveda Buddhism and gained a wide reputation not only in Central Asia but also in China

After he declined to come to Chang’an to serve a ruler at the time, he was forcibly taken to inside the Chinese border by the ruler’s army (382 CE) and stayed 18 years near the border even after the ruler himself was disposed

In 401 CE he was taken to Chang’an by a new ruler and provided with a team of 120 Chinese monks to assist him in translating the Mahayana Buddhist works

Over 600 volumes were completed during his time

He was credited for a new method of translation which is relevant even today

Founded a new school of Buddhist philosophy which resulted in a new sect

Admired as a genius, he was “ordered’ by the ruler to marry ten maidens so that his talent can be inherited

III. Chinese Monks to the West

A. Zhu Shiheng (c. 250 CE)

First Chinese monk to go west in search of true Buddhist scriptures

Confused about the Buddhist literature’s correctness and authenticity, went to Khotan (Yu-tian) to learn more

Obtained 90 volumes and sent them back to Luoyang after overcoming difficulties

Died in Khotan at age 80

B. Fa Hsian (Fa Xian)

Born in 334 and died in 420 C.E.

Decided to become a monk when his parents both died

First Chinese monk to go to India

He was 60 when he started his long journey in the company of 10 Chinese monks

Took 6 years to reach Central India, stayed there for 6 years to learn the language and the scriptures, 2 years in the south, including today’s Sri Lanka, and 1 year to return home by sea

Wrote “Buddist-Country Records” after his return, detailing his experiences

A compendium of Buddhist temples, practices, geography and history of Central Asia and Indian

C. Sung Yun

A native of Dunhuang, worked in the capital city of Luoyang in early 6th century

Was sent by the Empress Dowager of the ruling dynasty to the West to present gifts and seek better scriptures (518 CE)

Reached Khotan and the Pamirs by passing through many small states

IV. The Story of Xuan Zang

Born (602 CE) into a family of intellectuals and officials

Entered monastery at 13 and became a ordained monk at 21

Spending five years visiting many Buddhist scholars and learned major classical Buddhist works

Puzzled by differences in these works regarding the ways to reach nirvana, decided to seek truth from India despite the dangers and difficulties involved

Upon return he was offered a ministerial post but declined; was given resources by the Emperor to translate the books he brought back

His style was much more fluid and elegant than the previous translators

But he was far more than a translator of Buddhist scriptures

He compiled, with the help of his disciple, a book on the West at the request of the Tang Emperor and gave vivid and detailed accounts of some 138 states he had visited

He was also the founder of the new Buddhist school based on the new philosophy he had helped to form while in India

The Great Tang’s Records of the Western World (Ta-Tang-Si-Yu-Ki)

On Xuan Zang’s Return to Chang’an

Xuan Zang stated that he saw this and described its precise location

Archeological work was done in early 20 century to uncover it

Asoka’s Pillar near the birthplace of Buddha

Erected around 300BCE; excavated around 1910

V. Impact of Buddhism in China

Introduced into China in the turbulent times in Chinese history; gained acceptance and grew in influence during the 400 years of turmoil in northern China

Buddhism, along with Taoism, provided comfort and a hope of after-life to people who suffered

Many rulers of the northern regimes were non-Han; they needed a form of worship that was different from Confucianism and Taoism

As a result, Buddhism took Chinese a characteristic; Theraveda which focused more on the individual was overlooked, Mahayana which emphasized helping others to achieve nirvana become the standard Buddhism in China, hence, Korea, Japan and Vietnam

Buddhist and Chinese philosophy influenced each other, resulting in transformation of both; in terms of Buddhism, it was the Zen school of Buddhism

VI. Between Body and Soul

Biological being and social being

Instinctive being, intellectual being and emotive being

Religion of salvation and religion of transcendental meditation

For discussion: What motivated the early Buddhist monks and what gave them strength?

LECTURE 2 / 15 OCTOBER 2009

I. Prelude

A. General Remarks

1. History is a function of geography; take China as an example

2. To understand history it is necessary to study not only the historical documents, which often record political events, military conflicts and diplomatic treaties, but also archeological findings, which provide material proof of the way a certain group lived. Historians also have to concern themselves with art and literature, linguistics and anthropology, trade and commerce, religious beliefs and social customs, technological development and economic conditions. Most importantly, it is necessary to examine the causality between different events and the circumstances that either strengthened or weakened the causality.

B. Consequences of Alexander’s Eastward Thrust

1. The Greeks in Bactria: Agents of East-West cultural exchange and fusion.

2.The Yue-chi (Tocharians):The exiles who became accidental conquerors and propagators of Buddhism to Central Asia and China.

II. The Use of Horses by Nomadic Peoples

Domestication of the horse gave the chariot and horse-riding warriors a huge advantage in battle. Shepherds on horseback could supervise much larger herds than on foot. Horse was until the train the fastest means of transport and communication.

Speed of the horse made long-distance trading easier.

The nomads thus had a great advantage over the settled farmers and the cities and towns supported by the farmers.

D. Nomadic tribes are generally not amenable to large centrally administered political organizations; the most common type of organization is a loose tribal alliance under the leadership of a strong leader who comes from a strong and large tribe. With horses, the rate of intermingle among nomadic tribes increased greatly, enabling the nomadic peoples on the Eurasian steppes to have frequent changes in genetic and linguistic characteristics, belief systems and social customs. Of course, they also traded more frequently both with other nomadic groups and with the settled societies.

III. The North-South Rivalry

Nomadic and farming societies either traded or engaged in wars

A pattern: Across the Eurasian continent, the peoples along the East-West axis mostly traded; the peoples along the North-South axis often had confrontations. This was because the nomadic people in the north needed goods produced by the farming societies in the south and possessed the military means to take what they needed by force.

In addition to satisfying their own needs, the nomadic people also re-sold goods they obtained from one farming society to another farming society for profit.

D. The settled population often resorted to bribing the nomadic raiders to gain peace, generally with an amount which would make looting unattractive.

E. Some farming societies responded to the threat posed by the nomadic people by adopting the costumes and horse-back fighting techniques of the nomadic people and/or by constructing walls along the perimeter of defense to stop the mounted raiders. (King Wu-ling of Zhao during the Warring States Period in China did this in about 350 BCE.)

IV. Confrontations between Han and Xiong-Nu (Huni)

A. Xiong-Nu (often referred to in Europe as Huns) gained recognition around 400 B.C.E. in the Yinshan region in today’s Inner Mongolia, to the north of Hohhot, and became a threat to the settled Han people during the last years of the Warring States Period. They took advantage of the strife between Han and Chu following the demise of Qin Empire in late 3rd century B.C.E., threatening Han Dynasty in its first century.

B. The early Han emperors resort to marrying Han princesses to Xiong-Nu chiefs, but this did not give them lasting peace as Xiong-Nu often raided Han cities despite the peace treaties.

V. The Strategy of the Han Emperors

To launch military offensive against the Huns

To find allies in the Western Region against the Huns in order to cut off the supply lines of the Huns from the West

To acquire superior horses for the Han cavalry

VI. The Missions of Zhang Qian

First mission (138-127 BCE)

Second mission (116-114 BCE)

VII. The Impact of Zhang Qian’s Missions on the East-West Exchange

A. From China to the Western Regions

• Silk, metallurgy, Chinese medicinal herbs (including ginger)

• Chinese writing and administrative system

B. From Western Regions to China

• Horses, clover, walnut, cucumber, onion, garlic, etc.

• Buddhism, music, dance, acrobatics, etc.

VIII. The Impact of Zhang Qian’s Missions on the East-West Exchange

VIII. Relations between Han China and Egypt, Rome, Persia

A. With Ptolemaic Egypt

• Trade developed both through the Silk Road and the Sea Route

• Some Alexandrian merchants lived in Central China

• Many archeological finds show the extent of Chinese imports from Egypt (e.g., glassware)

B.With Roman Empire

• China and Rome learned the existence of each other during Han Dynasty;

• Silk was the main Chinese export and Rome was the largest importer;

• Glass utensils and decorative glass beads were imported to China, so was woolen material and amber.

C. With Parthian Persia

• Lute (pipa) and harp (konghou), two important music instruments in Chinese music, were both imported from Persia via Central Asia;

• Archeological finds include winged-beasts; documents mentioned that ostrich and lions from Africa came to China through Persia and Central Asia

• Some Buddhist monks of Persian origin came to China and introduced Buddhism to China

A. General Remarks

1. History is a function of geography; take China as an example

2. To understand history it is necessary to study not only the historical documents, which often record political events, military conflicts and diplomatic treaties, but also archeological findings, which provide material proof of the way a certain group lived. Historians also have to concern themselves with art and literature, linguistics and anthropology, trade and commerce, religious beliefs and social customs, technological development and economic conditions. Most importantly, it is necessary to examine the causality between different events and the circumstances that either strengthened or weakened the causality.

B. Consequences of Alexander’s Eastward Thrust

1. The Greeks in Bactria: Agents of East-West cultural exchange and fusion.

2.The Yue-chi (Tocharians):The exiles who became accidental conquerors and propagators of Buddhism to Central Asia and China.

II. The Use of Horses by Nomadic Peoples

Domestication of the horse gave the chariot and horse-riding warriors a huge advantage in battle. Shepherds on horseback could supervise much larger herds than on foot. Horse was until the train the fastest means of transport and communication.

Speed of the horse made long-distance trading easier.

The nomads thus had a great advantage over the settled farmers and the cities and towns supported by the farmers.

D. Nomadic tribes are generally not amenable to large centrally administered political organizations; the most common type of organization is a loose tribal alliance under the leadership of a strong leader who comes from a strong and large tribe. With horses, the rate of intermingle among nomadic tribes increased greatly, enabling the nomadic peoples on the Eurasian steppes to have frequent changes in genetic and linguistic characteristics, belief systems and social customs. Of course, they also traded more frequently both with other nomadic groups and with the settled societies.

III. The North-South Rivalry

Nomadic and farming societies either traded or engaged in wars

A pattern: Across the Eurasian continent, the peoples along the East-West axis mostly traded; the peoples along the North-South axis often had confrontations. This was because the nomadic people in the north needed goods produced by the farming societies in the south and possessed the military means to take what they needed by force.

In addition to satisfying their own needs, the nomadic people also re-sold goods they obtained from one farming society to another farming society for profit.

D. The settled population often resorted to bribing the nomadic raiders to gain peace, generally with an amount which would make looting unattractive.

E. Some farming societies responded to the threat posed by the nomadic people by adopting the costumes and horse-back fighting techniques of the nomadic people and/or by constructing walls along the perimeter of defense to stop the mounted raiders. (King Wu-ling of Zhao during the Warring States Period in China did this in about 350 BCE.)

IV. Confrontations between Han and Xiong-Nu (Huni)

A. Xiong-Nu (often referred to in Europe as Huns) gained recognition around 400 B.C.E. in the Yinshan region in today’s Inner Mongolia, to the north of Hohhot, and became a threat to the settled Han people during the last years of the Warring States Period. They took advantage of the strife between Han and Chu following the demise of Qin Empire in late 3rd century B.C.E., threatening Han Dynasty in its first century.

B. The early Han emperors resort to marrying Han princesses to Xiong-Nu chiefs, but this did not give them lasting peace as Xiong-Nu often raided Han cities despite the peace treaties.

V. The Strategy of the Han Emperors

To launch military offensive against the Huns

To find allies in the Western Region against the Huns in order to cut off the supply lines of the Huns from the West

To acquire superior horses for the Han cavalry

VI. The Missions of Zhang Qian

First mission (138-127 BCE)

Second mission (116-114 BCE)

VII. The Impact of Zhang Qian’s Missions on the East-West Exchange

A. From China to the Western Regions

• Silk, metallurgy, Chinese medicinal herbs (including ginger)

• Chinese writing and administrative system

B. From Western Regions to China

• Horses, clover, walnut, cucumber, onion, garlic, etc.

• Buddhism, music, dance, acrobatics, etc.

VIII. The Impact of Zhang Qian’s Missions on the East-West Exchange

VIII. Relations between Han China and Egypt, Rome, Persia

A. With Ptolemaic Egypt

• Trade developed both through the Silk Road and the Sea Route

• Some Alexandrian merchants lived in Central China

• Many archeological finds show the extent of Chinese imports from Egypt (e.g., glassware)

B.With Roman Empire

• China and Rome learned the existence of each other during Han Dynasty;

• Silk was the main Chinese export and Rome was the largest importer;

• Glass utensils and decorative glass beads were imported to China, so was woolen material and amber.

C. With Parthian Persia

• Lute (pipa) and harp (konghou), two important music instruments in Chinese music, were both imported from Persia via Central Asia;

• Archeological finds include winged-beasts; documents mentioned that ostrich and lions from Africa came to China through Persia and Central Asia

• Some Buddhist monks of Persian origin came to China and introduced Buddhism to China

HIST 48T/58L Updated Schedule

Lecture 1 (8 Oct 2009)

Alexander and his Eastern Thrust

Lecture 2 (15 Oct 2009)

Zhang Qian and the Opening of the Silk Road

Lecture 3 (22 Oct 2009)

Beauty of Loulan and the Tarim Basin During Han China

Lecture 4 (3 Nov 2009)

Buddhist Monks Bringing Scriptures to China (YD 106)

Lecture 5 (12 Nov 2009)

The Itinerant Sogdians

Lecture 6 (19 Nov 2009)

Battle of Talas – Midterm

Lecture 7 (24 Nov 2009)

Nestorians, Manicheans, Jews and Muslims in Tang & Song China (NH 202)

Lecture 8 (1 Dec 2009)

Mongol Rule

Lecture 9

Medieval Travelers

Lecture 10

The Timurids

Lecture 11

The Safavids and Uzbeks

Alexander and his Eastern Thrust

Lecture 2 (15 Oct 2009)

Zhang Qian and the Opening of the Silk Road

Lecture 3 (22 Oct 2009)

Beauty of Loulan and the Tarim Basin During Han China

Lecture 4 (3 Nov 2009)

Buddhist Monks Bringing Scriptures to China (YD 106)

Lecture 5 (12 Nov 2009)

The Itinerant Sogdians

Lecture 6 (19 Nov 2009)

Battle of Talas – Midterm

Lecture 7 (24 Nov 2009)

Nestorians, Manicheans, Jews and Muslims in Tang & Song China (NH 202)

Lecture 8 (1 Dec 2009)

Mongol Rule

Lecture 9

Medieval Travelers

Lecture 10

The Timurids

Lecture 11

The Safavids and Uzbeks

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)