Friday, January 1, 2010

FINAL EXAM

!!! Students will be responsible for the course content on blog plus class notes.

!!! Every student is expected to write a term paper.

FINAL REVIEW / 22 DECEMBER 2009

Outline

1. The Silk

2. The Silk Road

3. On the Silk Road

4. Cultural Exchanges on the Silk Road

5. Reflections on the Silk Road

East-West Exchanges Across the Eurasian Continent

A “steppe route” used by the nomadic peoples

A “sea route” used by the coastal seafarers

An “oasis route” used mainly by the sedentary people

The Silk Road

The Silk Road

Richthofen proposed the concept of the Silk Road (“Seidenstrasse”) in 1877

“The road that links China and Transoxanian (between Amu Darya and Syr Darya) as well as that which links China and India, with silk being the main commodity of trade”

Not a single road, but a network of roads

Travelers on the Silk Road 丝绸之路上的途人

1、张骞

2、鸠摩罗什

3、玄奘

4、成吉思汗

鸠摩罗什 Kumarajiva (344∼413 C.E.)

玄奘 Xuanzang (602-664 C.E.)

While in India 玄奘在印度

Painting in the Indian Parliament, commemorating Xuanzang’s stay in India and acknowledging his contributions to the Indian culture and historiography

The pagoda ordered by Emperor Taizong to house the scriptures Xuanzang brought back to China

A relic of the Buddha, Kushan Empire (2nd C.)

Excavated in early 20th century

Asoka’s Pillar near the birthplace of Buddha

Erected around 300B.C.E.

Excavated around 1910

Vanished Kingdoms on the Silk Road丝绸之路上消失的古国

Loulan 楼兰

Niya 尼雅(精绝)

Niya Site (精绝国遗址)

Some Residents on the Silk Road 丝绸之路上的一些居民

Tocharians 吐火罗人

Han 汉人

Qiangs 羌人

Sogdians 粟特人

Turks 突厥人

Mongols 蒙古人

Religions on the Silk Road 丝绸之路上的宗教

1. Buddhism 佛教

2. Zoroanstrianism 祆教

3. Manichaeism 摩尼教

4. Nestorianism 景教

5. Islam 伊斯兰教

Gandhara Art 犍陀罗艺术

Buddhists in India originally did not have images of Buddha, believing that it was impossible to portray him.

Buddhists in Bactria felt a need to worship Buddha with human features. Hence, they applied the Greek sculpture and painting techniques to Buddha and other deities.

The Story of Paper 纸的故事

Paintings on the Silk Road丝绸之路上的绘画

Stories of Writing Systems 文字的故事

Transformations of the Phoenician Alphabet

The Aramaic script

The Syriac script

The Sogdian script

The Uighur script

The Mongolian script

The Manchurian script

An Aramaic Inscription (3rd century B.C.E.) 阿拉美文石刻

Manuscript in Syriac Script 古叙利亚文写本

Letter Written in Sogdian Script (4th century)

粟特文书信

A Document in Uighur Script 回鹘文

Manchurian writing

满文

Khitan Characters 契丹文字

Tangut (Xi Xia) Characters 西夏文字

Jurchen (Nuzhen) Characters 女真文字

Tang Dynasty Document Unearthed in Caucasus 高加索出土的唐代文书

Reflections on the Silk Road 丝绸之路上的所见所思

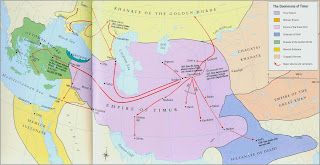

Communication in the 13th and 14th Centuries

Thank you!

LECTURE 10 / 22 DECEMBER 2009

Outline

Historical Significance of the Westward Migration of the Mongols

Timur—Scorch of God

The Timurids and Renaissance of Perso-Islamic Culture

The Uzbeks

Miniature Painting and “My Name Is Red”

Significance of the Westward Migration of the Mongols

Timur: Scorch of God

The Descendents of Genghis Khan, or the “Golden Family”, enjoyed a special status in the lands once conquered by him; despite repeated and often rapid successions of political control, the rulers of Golden Horde, White Horde, the Ilkhanate, the Chaghatay all needed to claim lineage from Genghis Khan in order to establish legitimacy.

Many Mongols became Islamized and Turkicized in the 14th century, but their claim to Mongol lineage continued for several centuries.

Timur was born in 1336 in today’s Uzbekistan, near Kesh in Transoxania, not far from Samarkand; he came from an affiliated Mongol tribe which contributed to Genghis Khan conquest of Transoxania in the 12th century; he was married to two women, both of prominent Mongol lineage.

Through personal and tribal alliances, Timur seized political power in 1370 in the western part of Chaghatay Khanate, including Transoxania.

He then conquered Khurasan, Khwarazm, Northwest India, Persia, and part of Asia Minor.

A skillful and effective political as well as military leader, exercising power ruthlessly, Timur was likened to Genghis Khan and known as Scorch of God.

Handicapped by his lack of a legitimate “Golden Family” claim, he was only de facto ruler of the empire he established, using the title “Emir” while manipulating a number of Khans throughout his 40-year career.

He liked his grandson Ulug Beg the most, giving him a thorough education while taking him along in many of the campaigns.

Noteworthy of his campaigns were the sacking of Delhi, Nishapur, Isfahan, and his incursion into Asia Minor.

In Asia Minor, he captured Bayazid Sultan and forced the Ottomans to face eastward, effectively giving relief to the Byzantine Empire which was under threat by the Ottomans; this caused the rulers in Italy and Spain to propose an alliance with Timur.

He maintained a cordial relationship with Ming China, sending several embassies to China and establishing direct lines of trade to by-pass Eastern Chaghatay and the remnants of Yuan Mongols.

In 1405, Timur switched his plan and turned to his “conquest of China”, but died in Otrar en route to China

He was buried in the mausoleum (Gur-e Emir) he built for himself

The Timurids and Renaissance of Perso-Islamic Culuture

Timur divided his empire into uluses among his sons and grandsons in a manner reminiscent of Genghis Khan’s bestowals.

Timur’s youngest son Shahrukh won the succession struggle and moved the capital from Samarkand to Herat; his own son Ulug Beg (1394-1449) ruled Transoxania.

Ulug Beg acted like a virtual monarch, visiting his father in Herat only rarely and irregularly.

Fortunately, Ulug Beg was effective and well-respected in Transoxania. He built mosques, madrasas; patronized arts and sciences; built an observatory that was the most advanced in the entire world.

Ulug Beg himself was a mathematician and astronomer; having published an “astronomy table” that was the most accurate and detailed up to his time; he described the names and positions of more than 1019 stars.

He is said to have given lectures in the main madrasa which had a curriculum much broader than the conventional madrasas.

On the door of this madrasa there was an inscription: “It is the duty of every Muslim man and woman to pursue knowledge.”

Ulug Beg was a good scholar, a poor military leader and very bad political leader.

He was badly defeated when his started campaigns against the White Horde to the north and the Mogulistan to the south.

After the death of his father Shahrukh, he won the title of Khan with the help of his eldest son; but he assigned his younger son to be his heir, resulting in his own death at the hands of his enraged elder son.

However, his rule of Transoxania was a very good period, with low taxation on land and flourishing industry and commerce, including good trade relations with China.

A Tajik from near Bukhara, Khwaja Baha al-Din Naqshband (1318-89) founded a group with silent zikr instead of groups of dervishes chanting in unison; this tariqa later spread to all over the Silk Road and is still prevalent today.

Its influence was initially due to the support it received from the Timurid elite in Herat.

There was also another important tariqa, the Yasaviya.

Under the Timurids rule, both Persian literature and Turkic literature were advanced.

Jami, the ultimate master of classic Persian poetry, was the son of a professor at a madrasa in Herat; he later became a devote follower of Naqshbandi.

Mir Ali Shir (1441-1501), better known as Navoi, wrote in both Persian and Turki, demonstrating the latter’s prowess as a language for poetry. Together with Babur, the last of the Timurid rulers, Navoi was credited with starting a Turki literature tradition.

The Timurids also promoted miniature painting; the master painter, Bihzad (1450-1537) started in Herat but later moved to Tabriz.

Relationship with Ming China

Uzbeks Coming South in Late 14th Century

The Uzbeks

The White Horde occupied the land in the deep northern steppe, east of the Ural mountains.

The ruling house was descedent from Shiban, the fifth son of Juchi who was himself the eldest son of Genghis Khan; these nomadic Turko-Mongols were called Uzbeks.

In the middle of the 15th century, led by Abulkhayr (1412-68), the Uzbeks moved down from the Kipchak steppe to the northern shores of Syr Darya, poised to cross it.

Requested to help settle a dispute among the Timurids, Abulkhayr entered Transoxania but later withdrew.

His grandson, Muhammad Shibani invaded a weak Timurid empire in 1501, driving away the reigning Khan, Barbur, the great-great-grandson of Timur.

The Uzbeks later conquered Khwarazm, Khurasan and settled in many towns; they mixed with the Persian-speaking Tajiks who had been the urban dwellers under the Timurids and were likely the direct descendents of the Sogdians.

Barbur, on his part, moved south and established an even larger empire, the Mughal Empire in India.

Miniature Painting and “My Name Is Red”

LECTURE 9 / 16 DECEMBER 2009

Medieval Travelers

Outline

I. Qiu Chuji (1148-1227)

II. Yelu Chucai (1189-1244)

III. Marco Polo (1254-1324)

IV. Ibn Battuta (1304-1377)

Communication in the 13th & 14th Centuries

I. “Travels to the West” by Qiu Chuji

Leader of a major Taoist sect, Qiu Chuji had a wide following and was admired by many, including Genghis Khan.

The latter invited Qiu Chuji to join his first expedition to the west; Qiu Chuji obliged despite his advanced age (at 75).

While his followers took advantage of the new prestige to expand their religious sect, Qiu Chuji wrote a book on his westward travels.

II. Yelu Chucai (1189-1244)

Of royal Khitai descent, Yelu Chucai’s father served as a minister under Jin (of Nuzhen or Jurchen); gifted in literature, he was educated in Chinese but also fluent in Mongolian and liked by the Mongol ruler.

He accompanied the ruler in expeditions against Southern Song and into Central Asia.

Travels to the West bore witness to the warfare and living conditions in Central Asia in the 13th century

III. The Travels of Marco Polo

Mongol’s rule of the Eurasian continent facilitated trade between Europe and the East, indirectly benefiting trading states such as Venice, which, along with Genoa, was one the two wealthiest states in Europe.

Marco Polo was born into a wealthy Venetian family; his father Nicolo owned trading houses in Crimea and was fluent in Mongolian and on good terms with Mongol rulers of the Golden Horde.

Marco at age 17 went to Khanbali (Beijing) and was given various administrative posts in China.

Despite his desire to return to Italy, he stayed in China for 17 years.

Finally he was asked to escort a Mongol princess to be married to the Ilkhan; the voyage took 3 years; when the princess arrived at Hormuz, the fiance had died.

Marco Polo was later involved in a battle against Genoa and captured.

In prison, he told his story to a cellmate, the novelist Rustichello.

The result was the well-known book The Travels of Marco Polo.

Appendix: Chapter LVII from The Travels of Marco Polo

OF THE GRAND KHAN’S BEAUTIFUL PLLACE IN HE CITY OF SHANDU— OF HIS STUD OF WHITE BROOD-MARES, WITH WHOSE MILK HE PERFORMS AN ANNUAL SACRIFICE—OF THE WONDERFUL OPERATIONS OF THE ASTROLOGERS ON OCCATIONS OF BAD WEATHER—OF THE CEREMONIES PRACTISED BY THEM IN THE TWO DESCRIPTIONS OF RELIGIOUS MENDICANTS, WITH THEIR MODES OF LIVING.

Departing from the city last mentioned, and proceeding three days’ journey in a north-easterly direction, you arrive at a city called Shandu, built by the grand khan Kublai, now reigning. In this he caused a palace to be erected, of marble and other handsome stones, admirable as well for the elegance of its design as for gilt, and very handsome. It presents one front towards the wall; and from each extremity of the building runs another wall to such an extent as to enclose sixteen miles in circuit of the adjoining plain, to which there is no access but through the palace. Within the bounds of this royal park there are rich and beautiful meadows, watered by many rivulets, where a variety of animals of the deer and goat kind are pastured, to serve as food for the hawks and other birds employed in the chase, whose mews are also in the grounds.

The number of these birds is upwards of two hundred; and the grand khan goes in person, at least once in the week, to inspect them. Frequently, when he rides about this enclosed forest, he has one or more small leopards carried on horseback, behind their keepers; and when he pleases to give directions for their being slipped they instantly seize a stag, or goat, or fallow deer, which he gives to his hawks, and in this manner he amuses himself. In the certre of these grounds, where there is a beautiful grove of trees, he has built a royal pavilion, supported upon a colonnade of handsome pillars, gilt and varnished. Round each pillar a dragon, likewise gilt, entwines its tail, whilst its head sustains the projection of the roof, and its talons or claws are extended to the right and left along the entablature. The roof is of bamboo cane, likewise gilt, and so well varnished that no wet can injure it. The bamboos used for this purpose are three palms in circumference and ten fathoms in length, and being cut at the joints, are split into two equal parts, so as to form gutters, and with these (laid concave and convex) the pavilion is covered; but to secure the roof against the effect of wind, each of the bamboos is tied at the ends to frame. The building is supported on every side (like a tent) by more than two hundred very strong silken cords, and otherwise, from the lightness of the materials, it would be liable to oversetting by the force of high winds. The whole is constructed with so much ingenuity of contrivance that all the parts may be taken asunder, removed, and again set up, at his majesty’s pleasure. This spot he has selected for his recreation on account of the mild temperature and salubrity of the air, and he accordingly makes it his residence during three months of the year, namely, June, July, and August; and every year, on the twenty-eighth day of the moon, in last of these months, it is his established custom to depart from certain sacrifices, in the following manner.

It is to be understood that his majesty keeps up a stud of about ten thousand horses and mares, which are white as snow; and of the milk of these no person can presume to drink who is not of the family descended from Jengiz-khan, with the exception only of one other family, named Boriat, to whom that monarch gave the honourable privilege, in reward of valorous achievements in battle, performed in his own presence. So great, indeed, is the respect shown to these horses that, even when they are at pasture in the royal meadows or forests, no one dares to place himself before them, or otherwise to impede their movements. The astrologers whom he entertains in his service, and who are deeply versed in the diabolical art of magic, having pronounced it to be his duty, annually, on the twenty-eighth day of the moon in August, to scatter in the wind the milk taken from these mares, as a libation to all the spirits and idols whom they adore, for the purpose of propitiating them and ensuring their protection of the people, male and female, of the cattle, fowls, the grain and other fruits of the earth; on this account it is that his majesty adheres to the rule that has been mentioned, and on that particular day proceeds to the spot where, with his own hands, he is to make the offering of milk. On such occasions these astrologers, or magicians as they may be termed, sometimes display their skill in a wonderful manner, for if it should happen that the sky becomes cloudy and threatens rain, they ascend the roof of the palace where the grand khan resides at the time, and by the force of their incantations they prevent the rain from falling and stay the tempest; so that whilst, in the surrounding country, storms of rain, wind, and thunder are experienced, the palace itself remains unaffected by the elements.

. Those who offer miracles of this nature are persons of Tebeth and Kesmir, two classes of idolaters more profoundly skilled in the art of magic than the natives of nay other country. They persuaded the vulgar that these works are effected through the sanctity of their own lives and the merits of their penances; and presuming upon the reputation thus acquired, they exhibit themselves in a filthy and indecent state, regardless as well of what they owe to their character as of the respect due to those in whose presence they appear. They suffer their faces to continue always uncleansed by washing and their hair uncombed, living altogether in a squalid style. They are addicted, moreover, to this beastly and horrible practice, that when any culprit is condemned to death, the carry off the body, dress it on the fire, and devour it; but of persons who die a natural death they do not eat the bodies. Besides the appellations before mentioned, by which they are distinguished from each other, they are likewise termed baksi, which applies to their religious sect or order, -- as we should say, friars, preachers, or minors. So expert are they in their infernal art, they may be said to perform whatever they will; and one instance shall be given, although it may be thought to exceed the bounds of credibility. When the grand khan sits at meals, in his hall of state (as shall be more particularly described in the following book), the table which is placed in the centre is elevated to the height of about eight cubits, and at a distance from it stands a large buffet, where all the drinking vessels are arranged.

Now, by means of their supernatural art, they cause the flagons of wine, milk, or any other beverage, to fill the cups spontaneously, without being touched by attendants, and the cups to move through the air the distance of then spaces until they reach the hand of the grand khan. As he empties them, they return to the place from whence they came; emptied them, they return to the place from whence they came; and his is done in the presence of such persons as are invited by his majesty to witness the performance. These baksis, when the festival days of their idols draw near, go to the palace of the grand khan, and thus address him: “Sire, be it known to your majesty, that if the honors of the honours of a holocaust are not paid to our deities, they will in their anger afflict us with bad seasons, with blight to our grain, pestilence to our cattle, and with other plagues. On this account we supplicate your majesty to grant us a certain number of sheep with black heads, together with so many pounds of incense and of lignum aloes, in order that we may be enable to perform the customary rites with due solemnity.” Their works, however, are not spoken immediately to the grand khan, but to certain great officers, by whom the communication is made to him. Upon receiving it he never fails to comply with the whole of their request; and accordingly, when the day arrives, they sacrifice the sheep, and by pouring out the liquor in which the meat has been seethed, in the presence of their idols, perform the ceremony of worship.

In this country there are great monasteries and abbeys, so extensive indeed that they might pass for small cities, some of them containing as many as two thousand monks, who are devoted to the service of their divinities, according to the established religious customs of the people. These are clad in a better style of dress than the other inhabitants; they shave their heads and their beards, and celebrate the festivals of their ilos with the upmost possible solemnity, having bands of vocal music and burning tapers. Some of this class are allowed to take wives. There is likewise another religious order, the members of which are named sensim, who observe strict abstinence and lead very austere lives, having no other food than a kind of pollard, which they steep in warm water until the farinaceous part is separated from the bran, and in that state they eat it. This sect pay adoration to fire, and are considered by the others as schismatics, not worshipping idols as they do. There is a material difference between them in regard to the rules of their orders, and these last described never marry in any instance. They shave their heads and beards like the others, and wear hempen garments of a black or dull colour; but even if the material were silk, the colour would be the same. They sleep upon coarse mats, and suffer greater hardships in their mode of living than any people in the world. We shall now quit this subject, and proceed to speak of the great and wonderful acts of the supreme lord and emperor, Kublai-kaan.

Ibn Battuta's Trip: (1325 – 1326) From Tangier across North Africa to Alexandria, Egypt

Appendix: An Excerpt from The Travels of Ibn Battutah (Account of the sultan of Bursa)

Its sultan is Urkhan Bak, son of the Sultan Othman Chuq. This sultan is the greatest of the kings of the Turkmens and the richest in wealth, lands and military forces. Of fortresses he possesses nearly a hundred, and for most of his time he is continually engaged in making the round of them, staying in each fortress for some days to put it into good order and examine its condition. It is said that he has never stayed for a whole month in any one town. He also fights with the infidels continually and keeps them under siege. It was his father who captured the city of Bursa from the hands of the Greeks, and his tomb is in its mosque, which was formerly a church of the Christians.

We continued our journey to the city of Yaznik. It is now in mouldering condition and uninhabited except for a few men in Sultan Urkhan’s service. In it lives also his wife Bayalun Khatun, who is in command of them, a pious and excellent woman. I visited her and she treated me honourably, gave me hospitality, and sent gifts. Some days after our arrival the sultan came to this city. I stayed in it about forty days, on account of the illness of a horse of mine, but when I became impatient at the delay I left it behind and set out wit three of my companions, and a slave girl and two slave boys. We had no one with us who could speak Turkish and translate for us. We had a translator previously but he left us in this city.

After our departure from it we spent the night at a village called Makaja with a legist there who treated us well and gave us hospitality. On continuing our journey from this village we were preceded by a Turkish woman on a horse, and accompanied by a servant, who was making for the city of Yanija, while we followed her up. She came to a great river which is called Saqari, as though it took its name from Saqar (God preserve us from it). She went right on to ford the river, but when she was in the middle of it the horse sand with her and threw her off its back. The servant who was with her tried to rescue her, but the river carried them both away. There were some men on the opposite bank who threw themselves in and swam after them; they brought out the woman with a spark of life still in her, but the man had perished-God’s mercy on him. These men told us that the ford was below that place, so we went down to it. It consists of four balks of wood, tied together with ropes, on which they place the horses’ saddles and the baggage; it is pulled over by men from the opposite bank, with the passengers riding on it, while the horses are led across swimming, and that was how we crossed.

We came the same night to Kawiyah, where we lodged in the hospice of one of the Akhis. We spoke to him in Arabic, and he did understand him. We spoke to him I Arabic, and he did not undertand him. Then he said, ‘Call the doctor of the law, for he knows Arabic,’ so the legist came and spoke to us in Persian. We addressed him in Arabic, but he didn’t understand us, and said to the young brother in Persian, ‘Ishan arabi kuhna miquwan waman arabi naw midanam.’ IIshan means ‘these men’, kuhna means ‘old’, miquwan ‘they say’, naw ‘new’ and midanam ‘I know’. What the legist intended by this statement was to shield himself from disgrace, when they thought that he knew the Arabic.’ However, the young Brother thought that matters really were as the man of law said, and this did us good service with him. He showed us the utmost respect, saying ‘these men must be honourably treated because they speak the ancient Arabic language, which was the language of the Prophet (God bless and give him peace) and of his Companions.’ I did not understand what the legist said at that time, but I retained the sound of his words in my memory, and when I learned the Persian Language I understood its meaning.

We spend the night in the hospice, and the Young Brother sent a guide with us to Yanija, a large and fine township. We searched there for Akhi’s hospice and found one of the demented poor brothers. When I said to him, ‘Is this the Akhi’s hospice?’ he replied, ‘na’am’ [yes] and I was filled with joy at this, thinking that I had found someone who understood Arabic. But when I tested him further the secret came to light, that he knew nothing at all of Arabic except the word na’am. We lodged in the hospice, and one of the students brought us food, since the Akhi was away. We became on friendly terms with this student, and although he knew no Arabic he offered his services and spoke to the deputy governor of the town, who supplied us with one of his mounted men.